When we last checked in with [Bucket Mouse], he had just finished cramming a Game Boy Advance (GBA) SP motherboard into the body of the iconic Game Boy DMG-01, complete with an aftermarket IPS display. Unfortunately, after a few weeks of using the system, he ran into a few issues that sent him back to the drawing board.

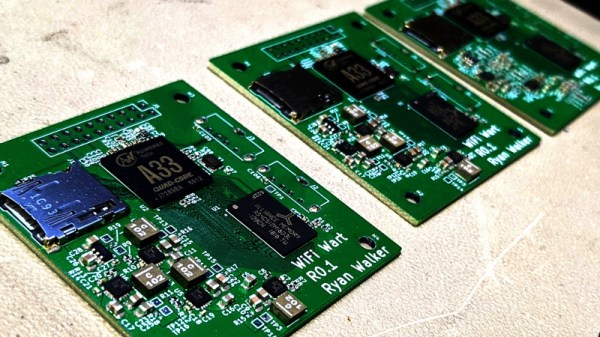

This time, he’s revamped Nintendo’s classic handheld with the internals from its successor, the Game Boy Color (GBC). Obviously that means this new build can’t play any GBA titles, but that was never actually the goal in the first place. It might seem obvious in hindsight, but owing to their general similarity, it ended up being far easier to fit the GBC hardware into the Game Boy’s shell. Though we still wouldn’t call this an “easy” swap by any stretch of the imagination…

Whether you want to follow his footsteps towards portable gaming bliss or just want to live vicariously through his soldering iron, [Bucket Mouse] has done an absolutely phenomenal job of documenting this build. While he cautions the write-up isn’t designed to be a step by step instructional piece, there’s an incredible wealth of information here for others looking to perform similar modifications.

Whether you want to follow his footsteps towards portable gaming bliss or just want to live vicariously through his soldering iron, [Bucket Mouse] has done an absolutely phenomenal job of documenting this build. While he cautions the write-up isn’t designed to be a step by step instructional piece, there’s an incredible wealth of information here for others looking to perform similar modifications.

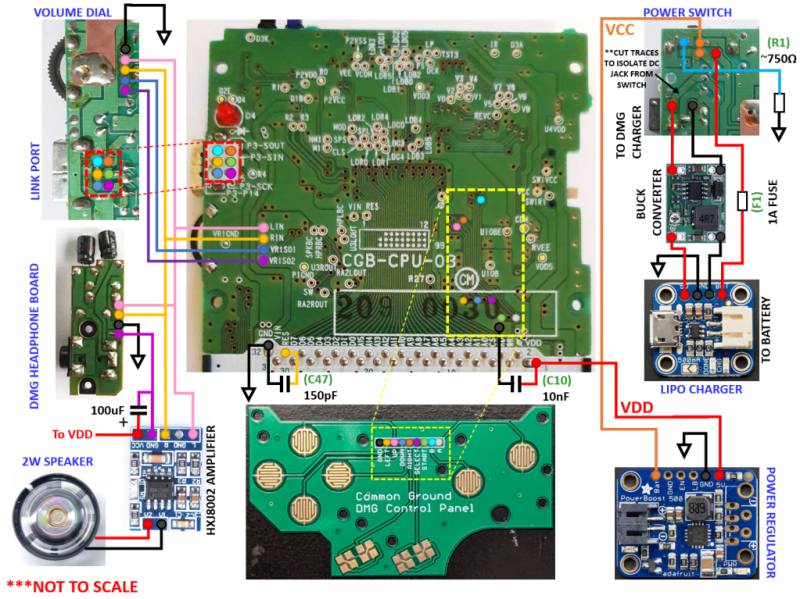

The build involved removing much of the original Game Boy’s connectors and controls, such as the volume wheel, Link Port, and even headphone jack, and grafting them onto a GBC motherboard that’s been physically trimmed down. At a high level it’s not unlike the trimmed Wii portables we’ve seen, but made much easier due to the fact the GBC only used a two-layer PCB. It also helps that [Bucket Mouse] has once again used an aftermarket IPS display, as that meant he could literally cut off the LCD driver section of the GBC motherboard. Of course there have also been several hardware additions, such as a new audio amplifier, power regulation system, LiPo charger, and 2000 mAh battery.

There’s a lot of fantastic details on this one, so if you’re remotely interested in what made the Game Boy and its successors tick, we’d highly recommend taking the time to read through this handheld hacking tour de force. His previous build is also more than worthy of some close study, even if it ended up being a bit ungainly in practice.