Like many people with multiple woodworking tools, [Will Stone] wanted to create a centralized dust collection system. But he quickly found that the devil was in the details, as he struggled to find an economic way to automatically kick on the vacuum when one of the tools started up. His final solution might be one of the most elegant, and surely the cheapest, we’ve ever come across.

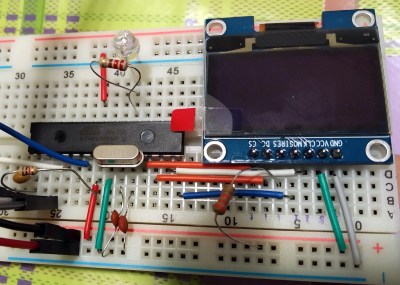

As with other DIY systems we’ve seen over the years, [Will] is using a simple inductive current sensor to detect when AC power is being drawn by one of his tools. But where the similarity stops is that there’s nothing so pedestrian as a microcontroller reading the output of the sensor. He realized that when the coils in the sensor were energized they were putting out about 7 volts AC, which should be more than enough to trigger a relay.

As with other DIY systems we’ve seen over the years, [Will] is using a simple inductive current sensor to detect when AC power is being drawn by one of his tools. But where the similarity stops is that there’s nothing so pedestrian as a microcontroller reading the output of the sensor. He realized that when the coils in the sensor were energized they were putting out about 7 volts AC, which should be more than enough to trigger a relay.

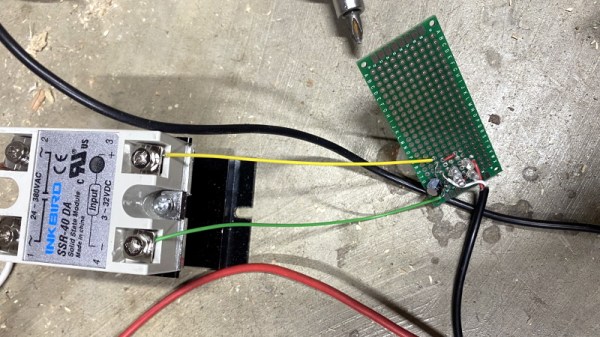

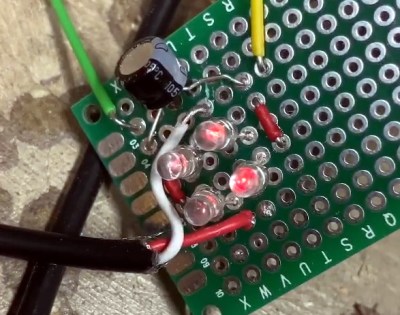

So he threw together a rectifier circuit on a piece of perfboard, using four LEDs in true hacker style. With the addition of a capacitor to smooth out the voltage, this little circuit is able to trip the 40 amp solid state relay controlling power to the vacuum using nothing more than the energy harvested from the sensor’s coil.

Using a current sensor is great when the tools are close enough to all be plugged into the same line, but that doesn’t help the folks with cordless tools or supersized shops. In that case, you might need to look into a sound-activated system.