Scanning Tunneling Microscopes (STMs) are amazing tools which can manipulate singular atoms, but they cannot characterize these atoms as they act only on the outer electron shell. Meanwhile X-ray spectroscopy is a great tool for characterizing materials, but has so far been unable to scale down to singular atoms. This is where a recent study (paywalled, see summary article) by Tolulope M. Ajayi and colleagues demonstrates how both STM and X-rays can be combined in order to characterize singular atoms.

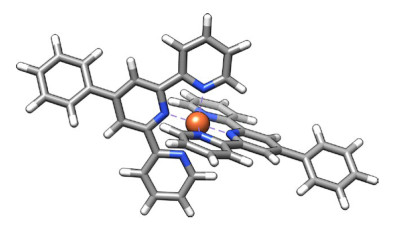

This research builds on previous research on synchrotron X-ray STM (SX-STM) which has been used for nanoscale imaging since 2009, but not down to the scale of a singular atom yet. Key to this achievement was to synthesize supramolecular complexes that could act as ‘tweezers’ to hold the atom under investigation in place and away from atoms of the same species. This not only allowed the atom to be identified using SX-STM, it also demonstrated that more subtle chemical properties of the atom can be analyzed in this manner, such as the way it interacts with other atoms.

The information gleaned this way matches up with what we know about the two atoms used in the study: iron and the rare earth terbium, with the latter’s lack of hybridization of its f orbitals (ℓ = 3) observable. For less well-studied atoms this method could provide a very efficient way to get a detailed overview of its properties. What is more, in future studies the researchers hope to use polarized X-rays to also obtain information about an atom’s spin state, opening interesting possibilities in areas such as spintronics and memory technologies.

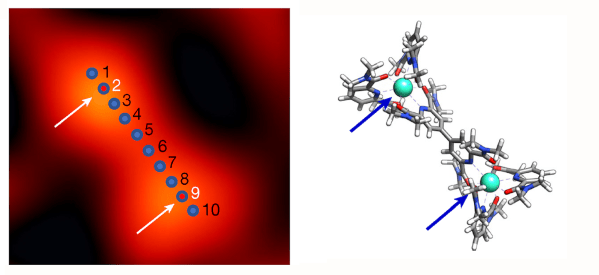

Heading image: As the tip was scanned across ten positions in a sample containing two terbium atoms, it picked a signal only from the positions (2 and 9) where terbium was located (left: STM image; right: sketch of the corresponding molecular structure). (Credit: Ajayi et al, 2023)