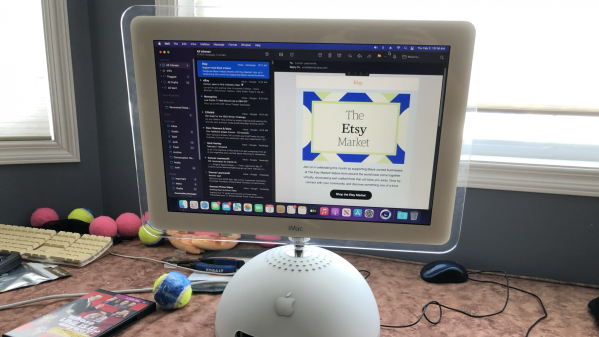

The second-generation iMac was a big departure from the original brightly-colored release. The chunky CRT aesthetic was dead, replaced with a sleek design featuring a slim LCD monitor on a floating arm. [Connor55] recently laid his hands on such a machine, and decided it needed a transplant of some modern M1 hardware.

The machine, as it came into his possession, lacked WiFi, and had a disc drive struggling to open its own tray, so it made a good candidate for hacking. Out came the original motherboard and drives, leaving room for a motherboard from a Mac Mini to be substituted in, with the powerful new M1 system-on-chip onboard.

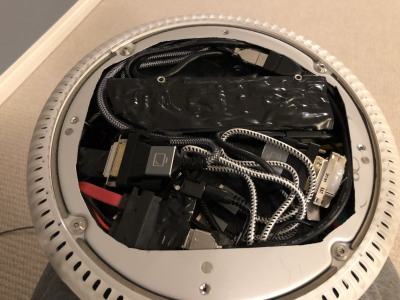

First up, the screen had to be converted to use DVI input, with a guide from [Dremel Junkie] helping out with that. The Mac Mini motherboard was then prepped to install in the iMac’s dome-shaped housing; notably, the entire board is smaller than the stock iMac G4’s hard drive. It still took plenty of cramming, with a multitude of adapters finagled and massaged to fit inside the original housing.

It’s a very completionist build; even features like the original power button and optical drive still work. It took some fiddling, but the display and backlight operate properly as per the original functionality, too.

Apple’s tasteful industrial design has always proved popular with modders. We’ve seen similar builds before over the years, from Intel NUCs stuffed into G4 iMacs to classic Macs outfitted with iPad hardware. It’s always satisfying to see vintage hardware given a new lease of life with modern grunt!