That sound you may have heard in the wee hours of Christmas morning had nothing to do with Santa; rather, it was the sound of a million astronomers collectively letting out their breath around the world as the James Webb Space Telescope survived its fiery ride to space. And not only did it survive, but the ESA launch team did such a good job putting the Ariane rocket on course that NASA predicts the observatory now has enough fuel to more than double its planned ten-year mission. Everything about the deployment process seems to be going well, too, with all the operations — including the critical unfurling of the massive and delicate sunshield — coming off without a hitch. Next up: tensioning of the multiple layers of the sunshield. If you want to play along at home, NASA has a nice site set up to track where JWST is and what its current status is, including temperatures at various points on the telescope.

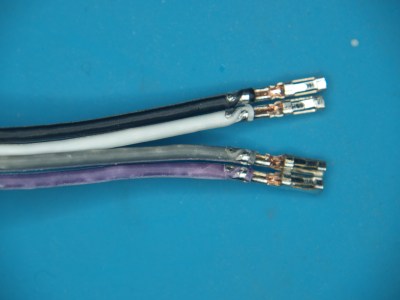

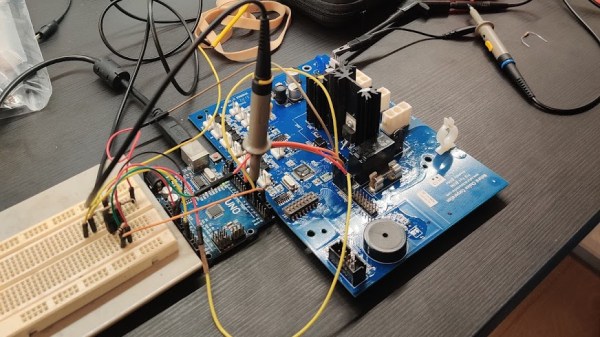

We got a tip from Mark about some dodgy jumper wires that we thought we should share. Low-quality jumpers aren’t really a new problem, but they can really put a damper on the fun of prototyping. The ones that Mark found could be downright dangerous. He got them with a recent dev board purchase; outwardly, they appear fine, at least at first. Upon closer inspection, though, the conductors have turned to powder inside the insulation. Even the insulation is awful, since it discolors when even slightly flexed. He suspects conductors are actually copper-plated aluminum; check out his pictures below and maybe look through your collection for similarly afflicted jumpers.

Speaking of dodgy hardware, if you love the smell of melting MOSFETs in the morning, then have we got a deal for you. It seems that a non-zero number of Asus Z690 Hero PC motherboards have suffered a fiery demise lately, stirring complaints and discontent. This led some curious types to look for the root cause, which led to the theory that an electrolytic cap had been installed with the wrong polarity on the dead boards. Asus confirmed the diagnosis, and is doing the right thing as they are “working with the relevant government agencies on a replacement program.” So if you’ve got one of these motherboards, you might want to watch the video below and see how the caps were installed.

If you’re in the mood for some engineering eye-candy, check out the latest video from Asianometry. They’ve got a finger on the pulse of the semiconductor industry, with particular attention paid to the engineering involved in making the chips we all have come to depend on. The video below goes into detail on the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) light source that fabrication machine maker ASML is developing for the next generation of chip making. The goal is to produce light with a mind-bending wavelength of only 13.5 nanometers. We won’t spoil the details, but suffice it to say that hitting microscopic droplets of tin with not one but two lasers is a bit of a challenge.

And finally, bad luck for 38 people in Tokyo who were part of a data breach by the city’s Metropolitan Police Department. Or rather, good luck since the data breach was caused by the loss of two floppy disks containing their information. The police say that there haven’t been any reports of misuse of the data yet, which is really not surprising since PCs with floppy drives are a little thin on the ground these days. You’d think that this would mean the floppies were left over from the 90s or early 2000s, but no — the police say they received the disks in December of 2019 and February of 2021. We’d love to know why they’re still using floppies for something like this, although it probably boils down to yet another case of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”