In the world of physics research, graphene has been gaining popularity as one of the most remarkable materials in the last 15 years. While it may appear unassuming in common household goods such as pencil leads, the material boasts a higher strength than steel and a higher flexibility than paper. On top of all that, it is also ultra-light and an excellent conductor of electric current and heat.

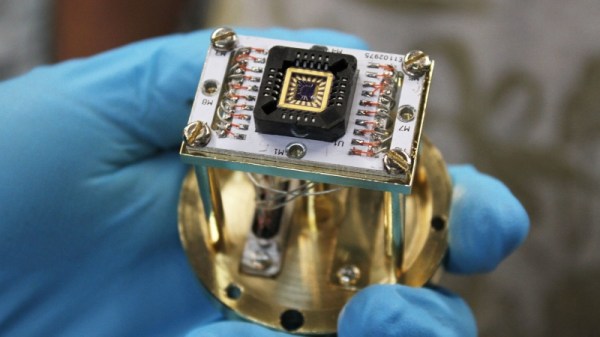

Recently, physicists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology discovered that stacking two sheets of graphene and twisting a small angle between them reveals an entire new field of material science – twistronics. In a paper published in Nature, researchers have taken a look into this new material, known as the magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. By modifying the graphene’s temperature, they were able to cause the material to shift from behaving like an insulator to transforming into a superconductor.

A graphic in the New York Times demonstrates some of the interesting properties that arise from stacking and twisting two sheets. Scientists have long known that graphene is a one-layer-thick honeycombed pattern of carbon atoms, but actually separating a single sheet of graphene has been fairly difficult. A low-tech method pioneered by two physicists at the University of Manchester involves using sticky tape to pull apart graphene layers until a single layer is left.

Small imperfections that arise from slightly misaligned sheets manifests in a pattern that allows electrons to hop between atoms in regions where the lattice line up, but unable to flow in regions that are misaligned. The slower moving electrons are thus more likely to interact with each other, becoming “strongly correlated”.

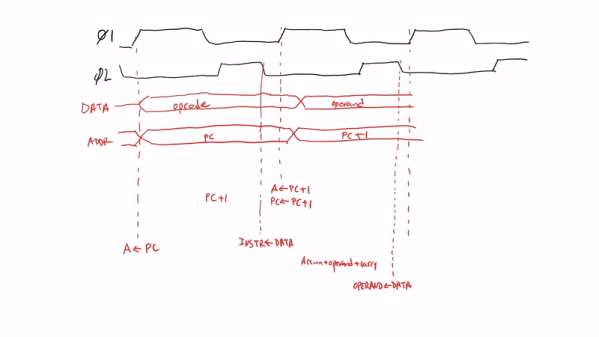

The technique for measuring the properties of this new twisted graphene is similarly low-tech. After a single layer of graphene is separated by sticky tape, the tape is torn in half to reveal two halves with perfectly aligned lattices. One of the sides is rotated by about 1.3 degrees and pressed onto the other. Sometimes, the layers would snap back into alignment, but other times they would end up at 1.1 degrees and stop rotating.

When the layers were cooled to a fraction of a degree above absolute zero, they were observed to become a superconductor, an incredibly discovery for the physicists involved in the experiment. Further studies showed that different permutations of temperature, magnetic field, and electron density were also able to turn the graphene into a superconductor. On top of this, the graphene was also able to exhibit a form of magnetism arising from the movement of electrons rather than the intrinsic properties of the atoms. With so many possibilities still unexplored, it’s certain that twistronics will reveal some remarkable findings pretty soon.

[Thanks Adrian for the tip!]