Showing robots adversarial behavior may be the key to improving their performance, according to a study conducted by the University of Southern California. While a generative adversarial network (GAN), where two neural networks compete in a game, has been demonstrated, this is the first time adversarial human users have been used in a learning effort.

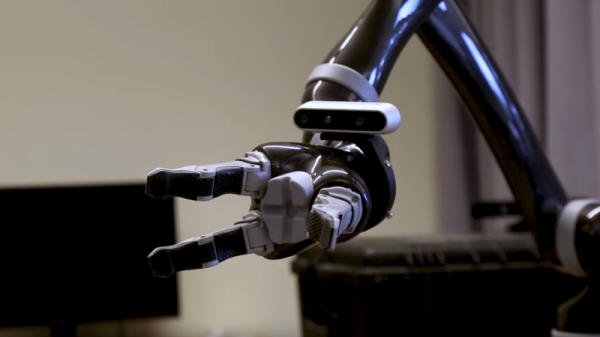

The report was presented at the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, describing the experiment in which reinforcement learning was used to train robotic systems to create a general purpose system. For most robots, a huge amount of training data is necessary in order to manipulate objects in a human-like way.

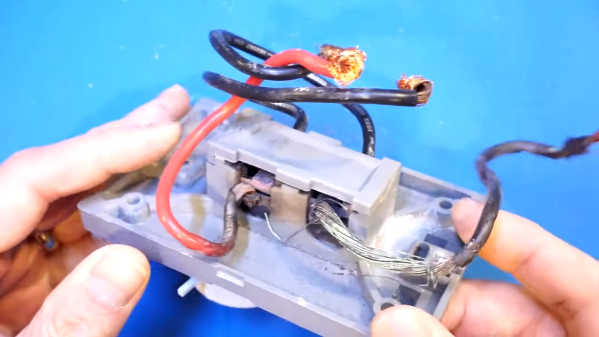

A line of research that has been successful in overcoming this problem is having a “human in the loop”, in which a human provides feedback to the system in regards to its abilities. Most algorithms have assumed a cooperating human assistant, but by acting against the system the robot may be more inclined to develop robustness towards real world complexities.

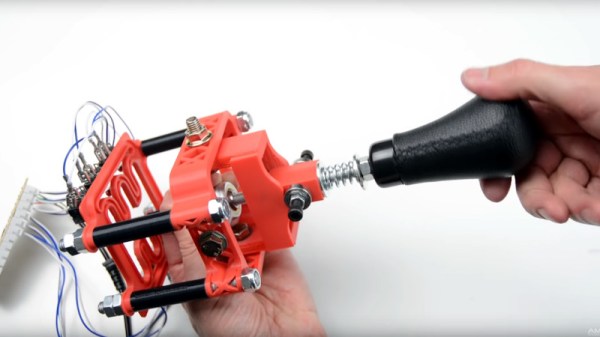

The experiment that was conducted involved a robot attempting to grasp an object in a computer simulation. The human observer observes the simulated grasp and attempts to snatch the object away from the robot if the grasp is successful. This helps the robot discern weak and firm grasps, a crazy idea from the researchers that managed to work. The system trained with the adversary rejected unstable grasps, quickly learning robust grasps for different objects.

Experiments like these can test the assumptions made in the learning task for robotic applications, leading to better stress-tested systems more inclined to work in real-world situations. Take a look at the interview in the video below the break.

Continue reading “It Turns Out, Robots Need Tough Love Too” →