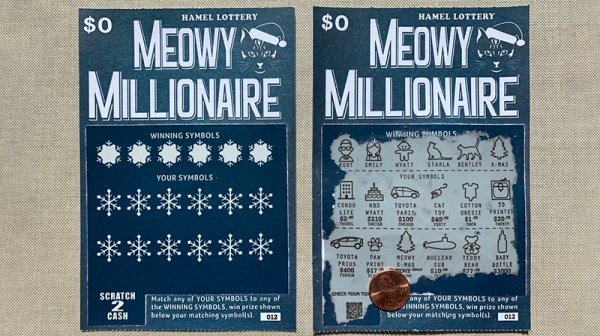

The lottery is to some a potential bonanza, to others a tax on the poor and the stupid. The only sure-fire way to win a huge fortune in the lottery does remain to start with an even bigger fortune. Nevertheless, scratch-off tickets are the entertainment that keep our roads paved or something. [Emily] over on Instructables came up with a way to create your own scratch-off cards, and the process is fascinating.

For [Emily]’s scratchers, there are five layers of printing on the front of the card. From back to front, they are the gray ‘security confusion layer’ printed with a letterpress, black printing for the symbols and prize amounts, also printed on a letterpress, a scratch-off surface placed onto the card with a Silhouette cutter, the actual graphics on the card, printed in blue with a letterpress, and a final layer of clear varnish applied via screen printing. There’s a lot that goes into this, but the most interesting (and unique) layer is the actual scratch-off layer. You can just buy that, ready to cut on a desktop vinyl cutter. Who knew.

After several days worth of work, [Emily] had a custom-made scratcher, ready to sent out in the mail as a Christmas card. It’s great work, and from the video below we can see this is remarkably similar to a real scratch-off lottery ticket. Not that any of us would know what scratching a lottery ticket would actually be like; of course that’s only for the gullible out there, and of course none of us are like that, oh no. You can check out a video of the scratch-off being scratched off below.