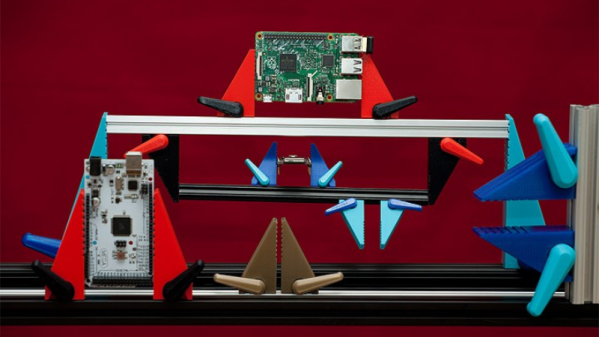

Over the last few years one thing has become abundantly clear: hackers love cramming the Raspberry Pi into stuff. From classic game systems to mirrors, there’s few places that haven’t been invaded by everyone’s favorite Linux SBC. From the inspired to the bizarre, we’ve brought such projects to your attention with minimal editorialization. As we’ve said before: it’s not the job of Hackaday to ask why, we’re here to examine how.

That said, some builds do stand out from the crowd. One such project is the “Pentesting BBU Dropbox” which [b1tbang3r] has recently posted to Hackaday.io. Noticing the battery bay in a cheap Cyberpower 350VA battery backup was just about the same size as the Raspberry Pi, he decided to convert it into a covert penetration testing device. Of course the illusion isn’t perfect as the battery backup function itself doesn’t work anymore. But if you hid this thing in an office or server room, there’s very little chance anyone would ever suspect it didn’t belong.

That said, some builds do stand out from the crowd. One such project is the “Pentesting BBU Dropbox” which [b1tbang3r] has recently posted to Hackaday.io. Noticing the battery bay in a cheap Cyberpower 350VA battery backup was just about the same size as the Raspberry Pi, he decided to convert it into a covert penetration testing device. Of course the illusion isn’t perfect as the battery backup function itself doesn’t work anymore. But if you hid this thing in an office or server room, there’s very little chance anyone would ever suspect it didn’t belong.

The key to the final device’s plausibility is that from stock it had dual RJ-11 jacks for analog modem surge protection. Swapping those jacks out for RJ-45 network connectors gives the BBU Dropbox an excuse to be plugged into the network. At a cursory glance, at least. Internally there is a TRENDnet Ethernet switch which allows the Pi to get on the network when an Ethernet cable is plugged into the battery backup.

We especially like the little details [b1tbang3r] put in to make the final device look as real as possible. The “Reset” button and “Wiring Fault” LED have been connected to the GPIO pins of the Pi, allowing for an exceptionally discrete user interface. For instance the LED could be setup to blink when a scan is complete, or the button could be used to wipe the device in an emergency.

This build reminds us of the Power Pwn released back in 2012 by Pwnie Express. That device was based around a relatively bulky power strip, and the only “feature” it looks like this DIY build is missing from the professional version is the $1,300 price.

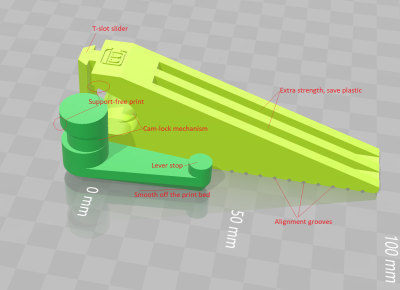

The typical hacker can never say no to more tools. And when it comes to clamps, one just can’t have enough of them. From holding small PCB’s to clamping together large sheets of plywood, you need a variety of sizes and quantities. So it would be pretty neat if we could just 3D print them whenever needed. [Mgx3d] has done that by designing

The typical hacker can never say no to more tools. And when it comes to clamps, one just can’t have enough of them. From holding small PCB’s to clamping together large sheets of plywood, you need a variety of sizes and quantities. So it would be pretty neat if we could just 3D print them whenever needed. [Mgx3d] has done that by designing