In one bad week in March, two people were indirectly killed by automated driving systems. A Tesla vehicle drove into a barrier, killing its driver, and an Uber vehicle hit and killed a pedestrian crossing the street. The National Transportation Safety Board’s preliminary reports on both accidents came out recently, and these bring us as close as we’re going to get to a definitive view of what actually happened. What can we learn from these two crashes?

There is one outstanding factor that makes these two crashes look different on the surface: Tesla’s algorithm misidentified a lane split and actively accelerated into the barrier, while the Uber system eventually correctly identified the cyclist crossing the street and probably had time to stop, but it was disabled. You might say that if the Tesla driver died from trusting the system too much, the Uber fatality arose from trusting the system too little.

But you’d be wrong. The forward-facing radar in the Tesla should have prevented the accident by seeing the barrier and slamming on the brakes, but the Tesla algorithm places more weight on the cameras than the radar. Why? For exactly the same reason that the Uber emergency-braking system was turned off: there are “too many” false positives and the result is that far too often the cars brake needlessly under normal driving circumstances.

The crux of the self-driving at the moment is precisely figuring out when to slam on the brakes and when not. Brake too often, and the passengers are annoyed or the car gets rear-ended. Brake too infrequently, and the consequences can be worse. Indeed, this is the central problem of autonomous vehicle safety, and neither Tesla nor Uber have it figured out yet.

Continue reading “Fatalities Vs False Positives: The Lessons From The Tesla And Uber Crashes” →

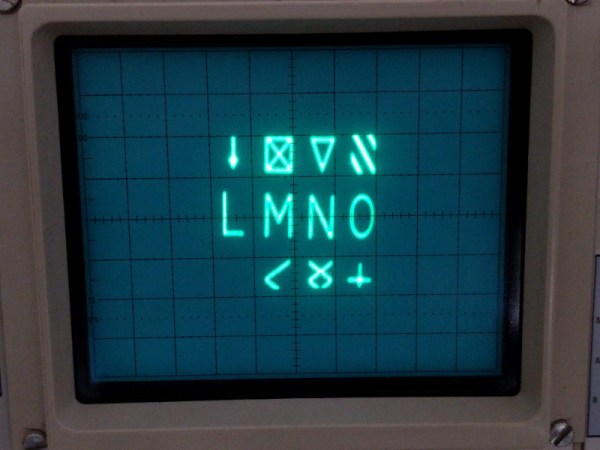

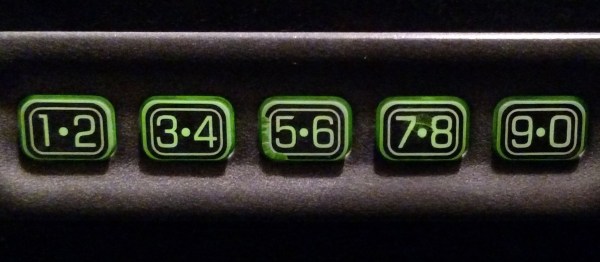

The electronics and mechanical part of this build are pretty simple. An acrylic frame holds five solenoids over the keypad, and this acrylic frame attaches to the car with magnets. There’s a second large protoboard attached to this acrylic frame loaded up with an Arduino, character display, and a ULN2003 to drive the resistors. So far, everything you would expect for a ‘robot’ that will unlock a car via its keypad.

The electronics and mechanical part of this build are pretty simple. An acrylic frame holds five solenoids over the keypad, and this acrylic frame attaches to the car with magnets. There’s a second large protoboard attached to this acrylic frame loaded up with an Arduino, character display, and a ULN2003 to drive the resistors. So far, everything you would expect for a ‘robot’ that will unlock a car via its keypad.