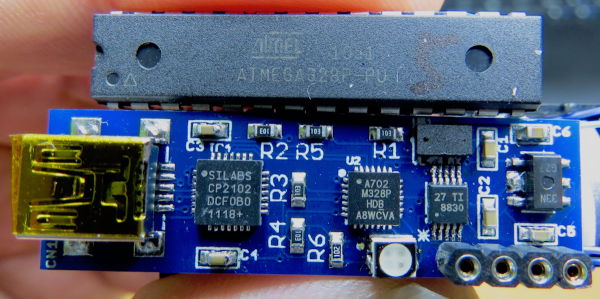

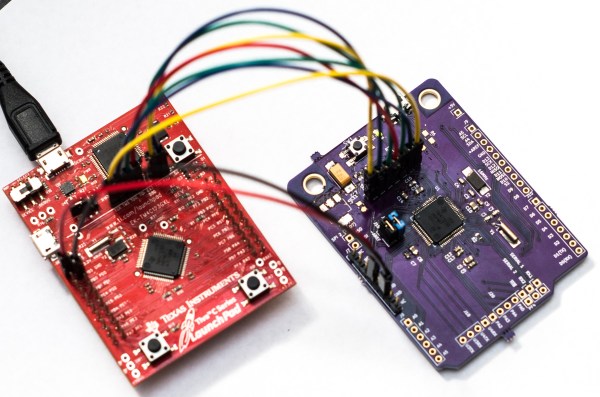

Texas Instruments’ Tiva C LaunchPad showcases TI’s ARM Cortex-M4F, a 32-bit, 80Mhz microcontroller based on the TM4C123GH6PM. The Tiva series of LaunchPads serve as TI’s equivalent of the Arduino Uno, and hovers at about the same price point, except with more processing power and a sane geometry for the GPIO pins.

The Tiva’s processor runs five times faster than standard ATMega328P, and it sports 40 multipurpose GPIO pins and multiple serial ports. Just like the Arduino has shields, the Tiva has Booster Packs, and TI offers a decent number of options—but nothing like the Arduino’s ecosystem.

[Jacob]’s Arduino-Tiva project, an entry in the Hackaday Prize, aims to reformat the Tiva by building a TM4C123GH6PM-based board using the same form 2″x 3″ factor as the Arduino, allowing the use of all those shields. Of course, an Arduino shield only uses two rows of pins, so [Jacob]’s board would position the spare pins at the end of the board and the shield would seat on the expected ones.

The finished project could be flashed by either the Arduino IDE or TI’s Energia platform, making it an easy next step for those who’ve already mastered Arduinos but are looking for more power.

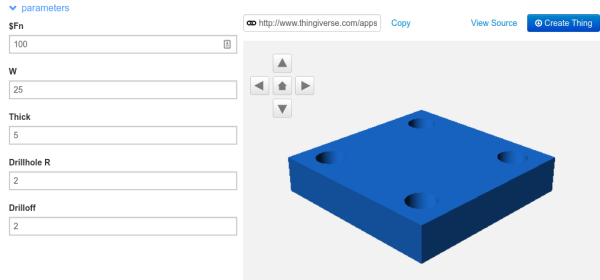

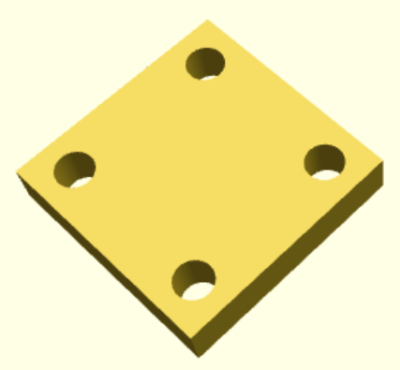

However, what if you have a general-purpose piece of code, and you want people to have the ability to customize it? For example, consider this code:

However, what if you have a general-purpose piece of code, and you want people to have the ability to customize it? For example, consider this code: