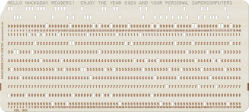

[John Graham-Cumming] might not be the first person to thumb through an old book and find an IBM punched card inside. But he might be the first to actually track down the origin of the cards. Admittedly, there were clues. The book was a Portuguese book about computers from the 1970s. The cards also had a custom logo on them that belonged to a computer school at the time.

It is hard to remember, but there was a time when cards reigned supreme. Sometimes called Hollerith cards after Herman Hollerith, who introduced the cards to data processing, these cards used square holes to encode information. Reading a card is simple. There are 80 columns on a classic card. If a column has a single punch over a number, then that’s what that column represents. So if you had a card with a punch over the “1” followed by a punched out “5” in the next column and a “0” in the column after that, you were looking at 150. No punches, of course, was a space.

So, how did you get characters? The two blank regions above the numbers are the X and Y zones (or, sometimes, the 11 and 12 zones). The “0” row was also sometimes used as a zone punch. To interpret a column, you needed to know if you expected numbers or letters. An 11-punch with a digit indicated a negative number if you were expecting a number. But it could also mean a particular letter of the alphabet combined with one or more punches in the same column.