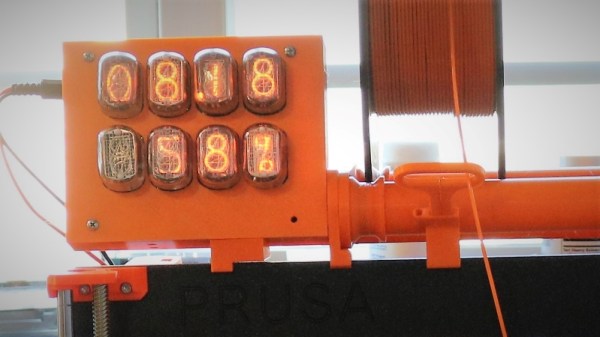

It might not be the kind of thing you’ve given much thought to, but if you’ve ever used a desktop 3D printer, it was almost certainly being controlled by an 8-bit CPU. In fact, the common RAMPS controller is essentially just a motor driver shield for the Arduino Mega. Surely we can do a bit better than that in 2019?

For his entry into this year’s Hackaday Prize, [Robert] is working on a 32-bit drop-in replacement board which would allow 3D printer owners to easily upgrade the “brain” of their machines. Of course, there are already a few 32-bit control boards available on the market, but these are almost exclusively high-end boards which can be tricky to retrofit into an older machine. It should also go without saying that they aren’t cheap.

For his entry into this year’s Hackaday Prize, [Robert] is working on a 32-bit drop-in replacement board which would allow 3D printer owners to easily upgrade the “brain” of their machines. Of course, there are already a few 32-bit control boards available on the market, but these are almost exclusively high-end boards which can be tricky to retrofit into an older machine. It should also go without saying that they aren’t cheap.

With this board, [Robert] is hoping to create a simpler upgrade path for 8-bit printer owners. Being small and cheap is already a pretty big deal, but perhaps equally importantly, his board is running the open source Marlin firmware. Marlin powers the majority of 8-bit desktop 3D printers (even if their owners don’t necessarily realize it) so sticking with it means that users shouldn’t have to change their software configuration or workflow just because they’ve upgraded their controller.

The board is powered by a 72 MHz STM32F103 chip, and uses state-of-the-art Trinamic TMC2208 stepper drivers to achieve near silent operation. The board has an automatic cooling fan to help keep itself cool, and with an XT60 connector for power, it should even be relatively easy to take your printer on the go with suitably beefy RC batteries.