Even though some devices now use WiFi and Bluetooth, so much of our home entertainment equipment still relies on its own proprietary infrared remote control. By and large (when you can find them) they work fine, but what happens when they stop working? First port of call is to change the batteries, of course, but once you’ve tried that what do you do next? [Hulk] has your back with this simple but effective IR Remote Tester / Decoder.

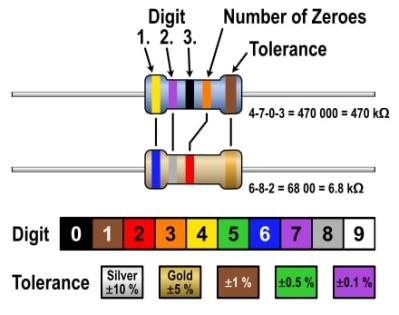

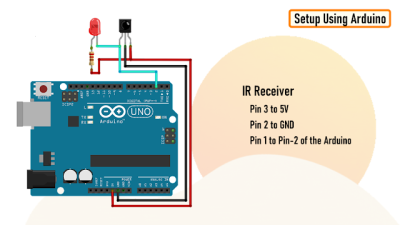

By using a cheap integrated IR receiver/decoder device (the venerable TSOP4838), most of the hard work is done for you! For a quick visual check that your remote is sending codes, it can easily drive a visible LED with just a resistor for a current-limit, and a capacitor to make the flickering easier to see.

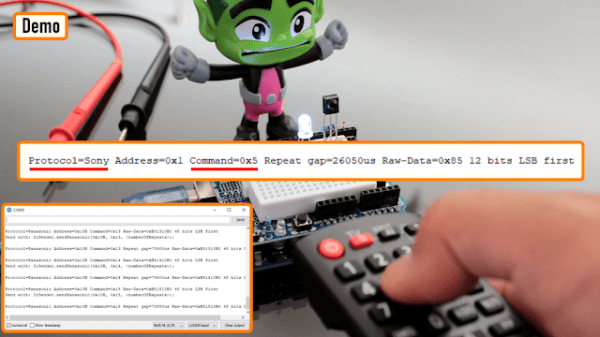

For an encore, [Hulk] shows how to connect this up to an Arduino and how to use the “IRremote” library to see the actual data being transmitted when the buttons are pressed.

It’s not much of a leap to imagine what else you might be able to do with this information once you’ve received it – controlling your own projects, cloning the IR remote codes, automating remote control sequences etc..

It’s a great way to make the invisible visible and add some helpful debug information into the mix.

We recently covered a more complex IR cloner, and if you need to put together a truly universal remote control, then this project may be just what you need.

Continue reading “IR Remote Tester Helps You Crack The Code”