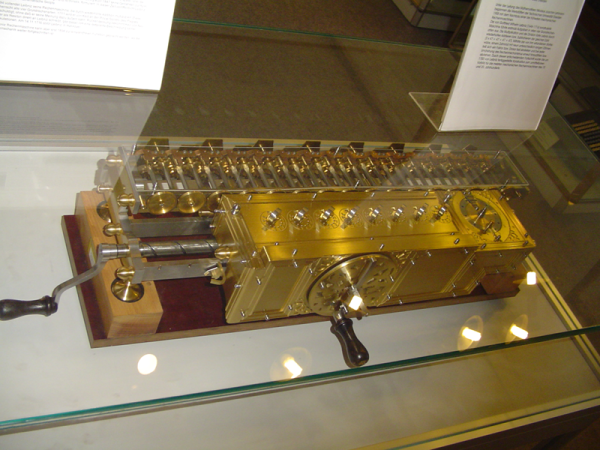

Earlier this year, [Dan Maloney] went inside mechanical calculators. Being the practical sort, [Dan] jumped right into the Pascaline invented by Blaise Pascal. It couldn’t multiply or divide. He then went into the arithmometer, which is arguably the first commercially successful mechanical calculator with four functions. That was around 1821 or so. But [Dan] mentions it used a Leibniz wheel. I thought, “Leibniz? He’s the calculus guy, right? He died in 1716.” So I knew there had to be at least a century of backstory to get to the arithmometer. Having a rainy day ahead, I decided to find out exactly where the Leibniz wheel came from and what it was doing for 100 years prior to 1821.

If you’ve taken calculus you’ve probably heard of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (who would have been 372 years old on July 1st, by the way). He’s the guy that gave us the notation we use in modern calculus and oddly was one of two people who apparently figured out calculus, the other being Issac Newton. Both men, by the way, accused each other of stealing, although it is more likely they both built on the same prior work. When you are struggling to learn calculus, it is sometimes amazing that not only did someone think it up, but two people thought it up at one time. However, Leibniz also built what might be the first four function calculator in 1694. His “stepped reckoner” used a drum and some cranks and the underlying mechanism found inside of it lived on until the 1970s in other mechanical calculating devices. Oddly, Leibniz didn’t use the term stepped reckoner but called the machine Instrumentum Arithmeticum.

If you’ve taken calculus you’ve probably heard of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (who would have been 372 years old on July 1st, by the way). He’s the guy that gave us the notation we use in modern calculus and oddly was one of two people who apparently figured out calculus, the other being Issac Newton. Both men, by the way, accused each other of stealing, although it is more likely they both built on the same prior work. When you are struggling to learn calculus, it is sometimes amazing that not only did someone think it up, but two people thought it up at one time. However, Leibniz also built what might be the first four function calculator in 1694. His “stepped reckoner” used a drum and some cranks and the underlying mechanism found inside of it lived on until the 1970s in other mechanical calculating devices. Oddly, Leibniz didn’t use the term stepped reckoner but called the machine Instrumentum Arithmeticum.

Many of us remember when a four function electronic calculator was a marvel and not even very inexpensive. Nowadays, you’d have to look hard to find one that only had four functions and simple calculators are cheap enough to give away like ink pens. But in 1694, you didn’t have electronics and integrated circuits necessary to pull that off.