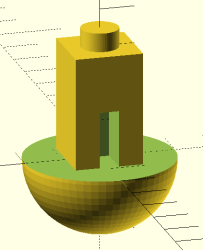

Have a look at the object to the right. Using a conventional fused deposition printer, how would you print the object? There’s no flat surface to lay on the bed without generating a lot of overhangs. That usually requires support.

In theory, you might be able to print the bottom of the sphere down, but it is difficult to get that little spot to adhere to the bed. If you have at least two extruders and you are set up to print support material, that might even be the best option. However, printing support out of the same material you are printing with makes it hard to get a good clean print. There is another possibility. It does require some post-processing, but then again, not as much as hacking away a bunch of support material.

In theory, you might be able to print the bottom of the sphere down, but it is difficult to get that little spot to adhere to the bed. If you have at least two extruders and you are set up to print support material, that might even be the best option. However, printing support out of the same material you are printing with makes it hard to get a good clean print. There is another possibility. It does require some post-processing, but then again, not as much as hacking away a bunch of support material.

A Simple Idea

The idea is simple and — at first — it will sound like a lot of trouble. The basic idea is to cut the model in half at some point where both halves would be easy to print and then glue them together. Stick around (no pun intended), though, because I’ll show you a way to make the alignment of the parts almost painless no matter how complex the object might be.

The practical problem with gluing together half models is getting the pieces in the exact position, but that turns out to be easy if you just make a few simple changes to your model. Another lesser problem is clamping a piece while gluing. You can use a vise, but some oddly-shaped parts are not conducive to traditional vise jaws.

In Practice

Starting with an OpenSCAD object, it is easy to cut the model in half. Actually, you could cut it anywhere. Then it is easy to rotate half of it so the cut line is at the bottom of each part. That doesn’t solve the alignment problem nor does it help you clamp when you glue.

The trick is to build a flange around each part. The flanges mate with a few screws after printing so alignment is perfect and bolts through the flange holes can keep the parts together and immobilized while your glue of choice sets. The kicker is that I even have an automated process to make the design side of this trick very easy.