Mozilla recently officially released their IoT platform. This framework comes with “Gateway” software that can run on a Raspberry Pi and a framework that can run on any number of devices.

As we’ve seen, IoT is a dubious prospect for consumers. When you throw in all the privacy issues, support issues, and end-of-life issues; it gets even worse. Nobody wants their light bulbs to stop working because a server in faraway land shut down, but that’s an hilariously feasible scenario.

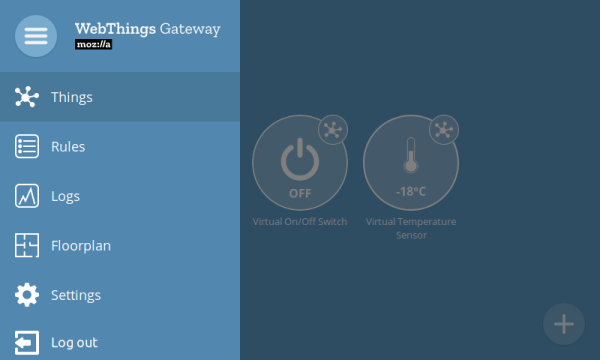

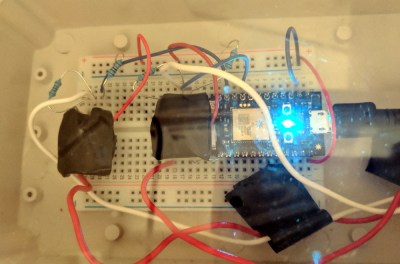

WebThings comes with a lot out of the box. It comes with a user interface, logging, rules, and an easy-to-understand API. Likewise the actual framework allows for building on many common devices and can be written in Node, Python, Java, Rust, Micropython, and used as an Arduino library. This opens it up for everything from a eBay ESP32 to a particle board.

We’ve started to notice some projects that use it trickling in on the tip line and on hackaday.io. We’re interested to see what kind of community grows around this, and are curious if it won’t be too long before easy-to-hack kits start showing up on your favorite online retailers.

There’s good documentation and of course, being open source, you can check out the source for yourself.