How do you prototype e-textiles? Any way you can that doesn’t drive you insane or waste precious conductive thread. We can’t imagine an easier way to breadboard wearables than this appropriately-named ThreadBoard.

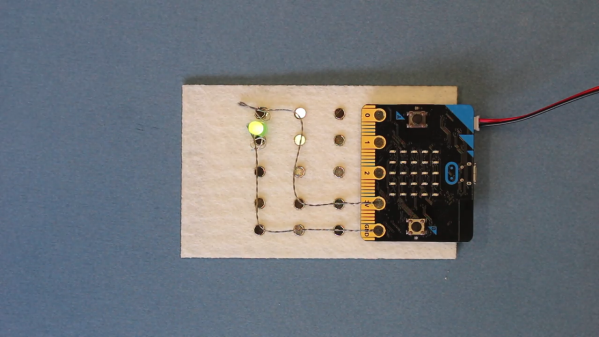

If you’ve never played around with e-textiles, they can be quite fiddly to prototype. Of course, copper wires are floppy too, but at least they will take a shape if you bend them. Conductive thread just wants lay there, limp and unfurled, mocking your frazzled state with its frizzed ends. The magic of ThreadBoard is in the field of magnetic tie points that snap the threads into place wherever you drape them.

The board itself is made of stiff felt, and the holes can be laser-cut or punched to fit your disc magnets. These attractive tie-points are held in place with duct tape on the back side of the felt, though classic double-stick tape would work, too. We would love to see somebody make a much bigger board with power and ground rails, or even make a wearable ThreadBoard on a shirt.

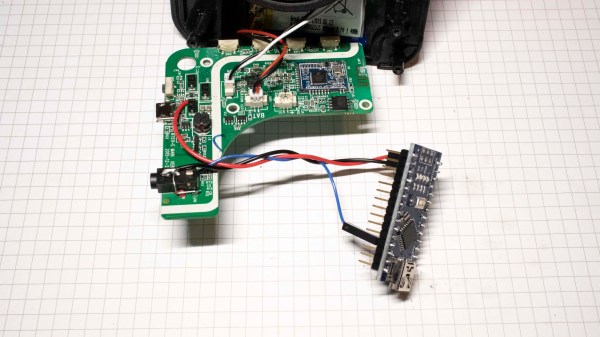

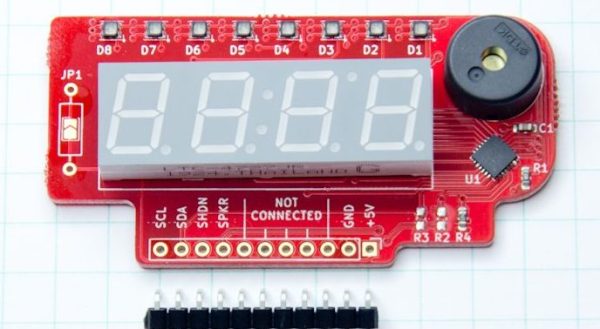

Even though [chrishillcs] is demonstrating with a micro:bit, any big-holed board should work, and he plans to expand in the future. For now, bury the needle and power past the break to watch [chris] build a circuit and light an LED faster than you can say neodymium.

The fiddly fun of e-textiles doesn’t end with prototyping — implementing the final product is arguably much harder. If you need absolutely parallel lines without a lot of hassle, put a cording foot on your sewing machine.

Continue reading “Magnets Make Prototyping E-Textiles A Snap”