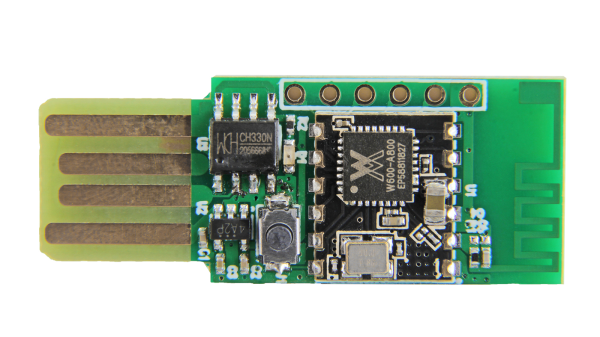

One of the biggest advantages of using the ESP8266 in your projects is how easy it is to get WiFi up and running. Just plug in the WiFi library, put the SSID and encryption key in your source code, and away you go. It authenticates with your network in seconds and you can get on with building your project. But things get a little trickier if you want to take your project someplace else, or distribute your source code to others. Quickly we learn the downside of using static variables for authentication.

While there are already a few solutions to this problem out there, [Martin Raynsford] wasn’t too thrilled with them. Usually they put the ESP8266 in Access Point mode, allow the user to connect, and then ask which network they should authenticate with. But he didn’t want his projects to require an existing network, and figured he could do just as well making a field-configurable AP.

While there are already a few solutions to this problem out there, [Martin Raynsford] wasn’t too thrilled with them. Usually they put the ESP8266 in Access Point mode, allow the user to connect, and then ask which network they should authenticate with. But he didn’t want his projects to require an existing network, and figured he could do just as well making a field-configurable AP.

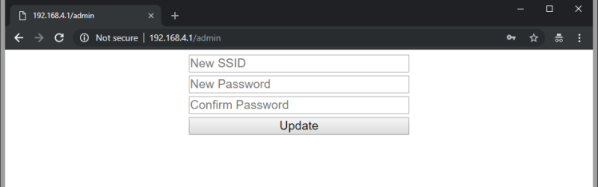

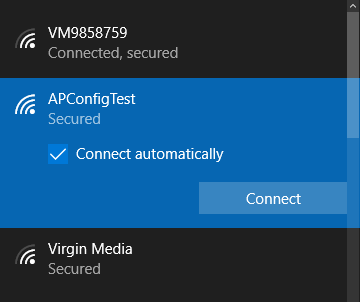

Using it is simple. Once the ESP8266 starts up it will create a new network in the form of “APConfig XXXXXX”, which should be easy enough to find from your client side device. Once connected, you can go to a simple administration page which allows you to configure a new AP name and encryption key. You even have the option to create an open AP by leaving the “Password” field blank. Once rebooted, the ESP8266 will create a new network with the defined parameters.

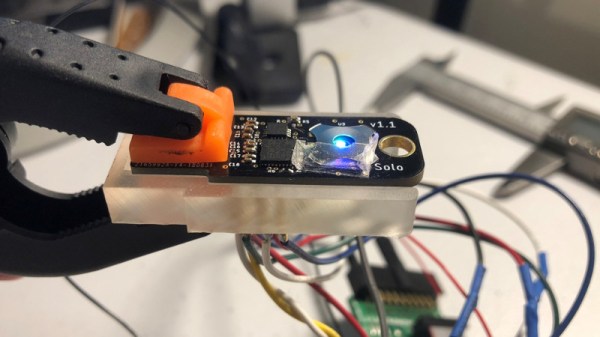

[Martin] has also included a “backdoor” to let anyone with physical access to the ESP8266 board create a new open AP that can be used to reconfigure the network settings. During boot up there is a brief period, indicated with specific blinks of the LED, wherein you can hit the reset button and trigger the open AP. This keeps you from getting locked out of your own project if you forget what key you gave it.

If you’re not one to go the austere route, take a look at some of the more robust solutions we’ve seen for easier end-user setup of the ESP8266.