It’s said that the electronic devices we use on a daily basis, particularly cell phones, could be so much smaller than they are if only the humans they’re designed for weren’t so darn big and clumsy. That’s only part of the story — battery technology has a lot to do with overall device size — but it’s true that chips can be made a whole lot smaller than they are currently, and are starting to bump into the limit of being able to handle them without mechanical assistance.

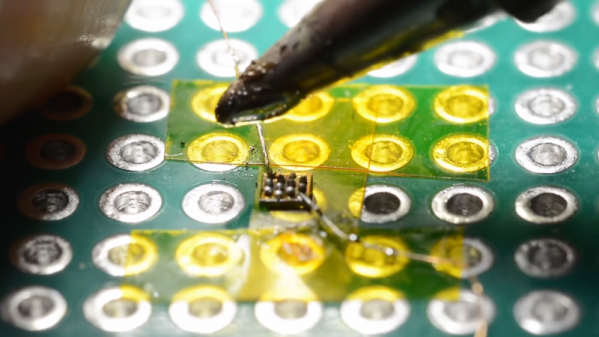

Or perhaps not, if [mitxela]’s hand-soldering of a tiny ball-grid array chip is any guide. While soldering wires directly to a chip is certainly a practical skill and an impressive one at that, this at least dips its toe into the “just showing off” category. And we heartily endorse that. The chip is an ATtiny20 in a WLCSP (wafer-level chip-scale package) that’s a mere 1.5 mm by 1.4 mm. The underside of the chip has twelve tiny solder balls in a staggered 4×6 array with 0.4 mm pitch. [mitxela] tackled the job of soldering this chip to a 2.54-mm pitch breakout board using individual strands from #30 AWG stranded wire and a regular soldering iron, with a little Kapton tape to hold the chip down. Through the microscope, the iron tip looks enormous, and while we know the drop of solder on the tip was probably minuscule we still found ourselves mentally wiping it off as he worked his way across the array. In the end, all twelve connections were brought out to the protoboard, and the chip powers up successfully.

We’re used to seeing [mitxela] work at a much larger scale, like his servo-plucked music box or a portable Jacob’s Ladder. He’s been known to get small before though, too, like with these tiny blinkenlight earrings.

Continue reading “No Caffeine, No Problem: A Hand-Soldered Chip-Scale Package”

The first chip from SiFive was the HiFive 1, which was based on the SiFive E31 CPU.

The first chip from SiFive was the HiFive 1, which was based on the SiFive E31 CPU.