Pinball still has that bit of magic that makes it stand out from first person shooters or those screen mashers eating up your time on the bus. The secret sauce is that sense of movement and feedback, and the loss of control as the ball makes its way through the play field under the power of gravity. Of course the real problem is finding a pinball machine. Pinbox 3000 is swooping in to fix that in a creative way. It’s a cardboard pinball machine that you build and decorate yourself.

We ran into them at Maker Faire New York over the weekend and the booth was packed with kids and adults all mashing flippers to keep a marble in play. The kit comes as flat-pack cardboard already scored and printed with guides for assembly which takes about an hour.

The design is quite clever, with materials limited to just cardboard, rubber bands, and a few plastic rivets. Both the plunger that launches the pinball and the flippers are surprisingly robust. They stand up to a lot of force and from the models on display it seems the friction points of cardboard-on-cardboard are the issue, rather than mechanisms buckling under the force exerted by the player.

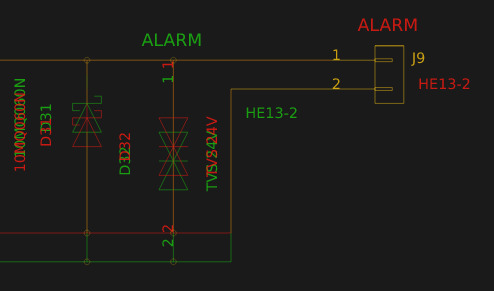

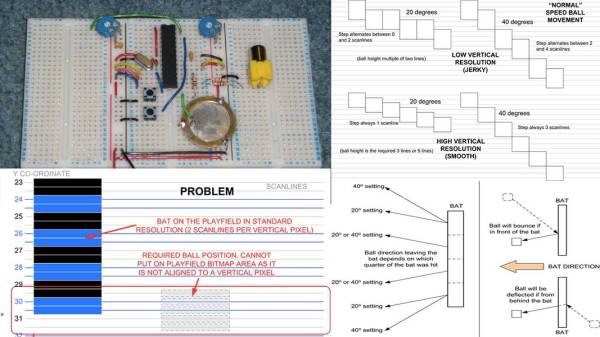

When first assembled the playfield is blank. That didn’t stop the fun for this set of kits stacked back to back for player vs. player action. There’s a hole at the top of playfields which makes this feel a bit like playing Pong in real life. However, where the kit really shines is in customizing your own game. In effect you’re setting up the most creative marble run you can imagine. This task was well demonstrated with cardboard, molded plastic packaging (which is normally landfill) cleverly placed, plus some noisemakers and lighting effects. The company has been working to gather up inspiration and examples for building out the machines. We love the multiple layers of engagement rolled into Pinbox, from building the stock kit, to fleshing out a playfield, and even to adding your own electronics for things like audio effects.

When first assembled the playfield is blank. That didn’t stop the fun for this set of kits stacked back to back for player vs. player action. There’s a hole at the top of playfields which makes this feel a bit like playing Pong in real life. However, where the kit really shines is in customizing your own game. In effect you’re setting up the most creative marble run you can imagine. This task was well demonstrated with cardboard, molded plastic packaging (which is normally landfill) cleverly placed, plus some noisemakers and lighting effects. The company has been working to gather up inspiration and examples for building out the machines. We love the multiple layers of engagement rolled into Pinbox, from building the stock kit, to fleshing out a playfield, and even to adding your own electronics for things like audio effects.

Check out the video below to see the fun being had at the Maker Faire booth.

Continue reading “This Pinball Game Doesn’t Come In A Box… It Is The Box”