When we think of 3D printed parts for our projects, most of us imagine little bits like brackets and mounting plates. Perhaps the occasional printed project enclosure. But if you’ve got a big custom printer as [Joshendy] does, plus plenty of time, it opens up a whole new world of large scale projects. Take for example the gorgeous RGB LED guitar body he recently completed.

Despite the considerable 300 x 300 mm build area of his custom 3D printer, [Joshendy] still had to design the guitar body in sections that could be bolted together after being printed in ABS. It took around 60 hours to run off all the parts, with the large central section taking the longest to print at 28 hours. With the generous application of heat-set inserts, the assembled guitar should be plenty strong.

While the skeletal plastic body of the guitar is certainly visually interesting in itself, it only makes up for half of the final look. Inside the central cavity, [Joshendy] has embedded two strips of RGB LEDs, a 128×64 OLED screen, and a custom PCB that plays host to a STM32L4 microcontroller the appropriate voltage regulators necessary to run it all on a battery pack.

The board taps into the audio being produced by the guitar and uses a fast Fourier transform (FFT) to get the LEDs reacting to the beat. As demonstrated in the video after the break, you can use the screen to navigate through the different lighting modes in real-time right on the instrument itself.

We covered the equally impressive large-format 3D printer that [Joshendy] used to produce this guitar earlier in the month, and it’s quite exciting to see the sort of things he’s printing on it already. This project has already set the bar very high, and we can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.

Continue reading “Illuminated 3D Printed Guitar Is Ready To Rock”

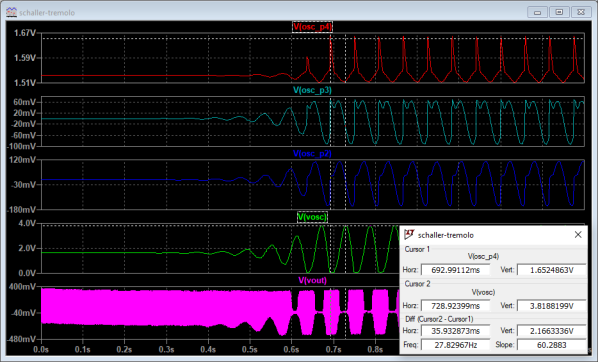

components and attenuating the low-frequency components. Of course, it’s fun to look at signals this way as well, especially when you can correlate shifts in sound quality to changes in the waveform and, ideally, the circuit that produces it.

components and attenuating the low-frequency components. Of course, it’s fun to look at signals this way as well, especially when you can correlate shifts in sound quality to changes in the waveform and, ideally, the circuit that produces it.