For years, [Michael Davis] has been using a large lead-acid battery to power the electronic components of his custom Dobsonian telescope; but that doesn’t mean he particularly enjoyed it. The battery was heavy, and you always had to be mindful of the wires connecting it to the scope. Looking to improve on the situation somewhat, he decided to build an adapter for Ryobi cordless tool batteries.

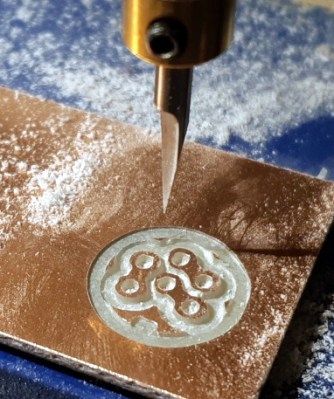

[Michael] had already seen similar 3D printed adapters, but decided to make his the traditional way. Well, sort of. He used a CNC router to cut out the distinctive shape required to accept the 18 V lithium-ion battery pack, but the rest was assembled from hardware store parts.

[Michael] had already seen similar 3D printed adapters, but decided to make his the traditional way. Well, sort of. He used a CNC router to cut out the distinctive shape required to accept the 18 V lithium-ion battery pack, but the rest was assembled from hardware store parts.

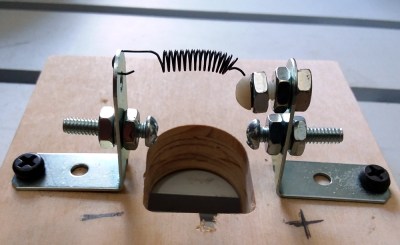

Bent mending plates with nuts and bolts were used to create adjustable contacts, and a spring added to the top ensures that there’s always a bit of tension in the system so it makes a good electrical contact. This setup makes for a very robust connector, and as [Michael] points out, the bolts make a convenient place to attach your wires.

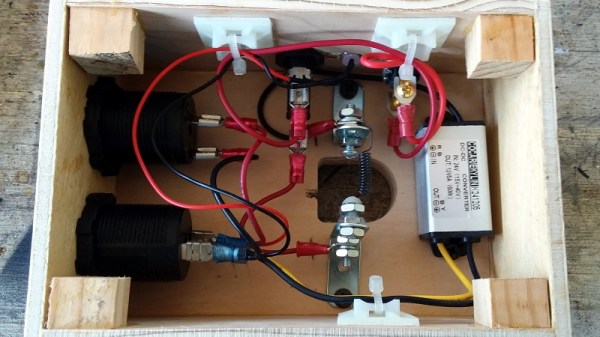

With the logistics of physically connecting to the Ryobi batteries sorted out, the next step was turning that into useful power for the telescope. A stable 12 V is produced by way of a compact DC-DC converter, and a toggle switch and fuse connect it to a pair of automotive-style power sockets. Everything is held inside of a wooden box that’s far smaller and lighter than the lead-acid monster it replaced, meaning it can get mounted directly to the telescope rather than laying on the ground.

If you want to build a similar adapter, the 3D printing route will potentially save you some time and effort. But we have to admit that the heavy-duty connection [Michael] has rigged up here looks quite stout. If you’ve got an application where the battery could be knocked around or vibrated lose, this may be the way to go.