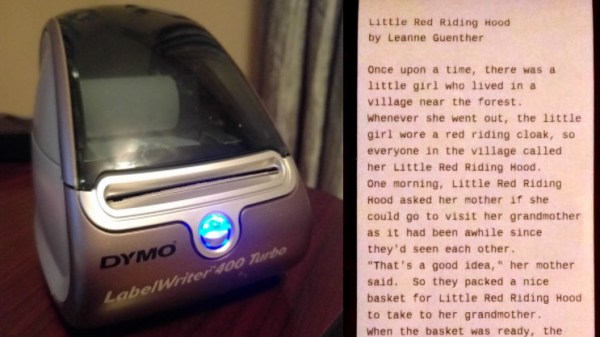

We know how it happens. You buy a fancy new label printer, thinking this is the answer to your disorganized space, but soon entropy grabs the printer as well, and it becomes just another item in the pile. When you find such items later, though, they can spark ideas. The idea that struck [Eric Nichols] was to turn his diminutive thermal printer into a dedicated one for short stories.

Inspired by an article about a vending machine that dispenses stories selected by the reader’s time constraints, [Eric] took on the task of getting his Dymo LabelWriter 400 Turbo working in this new capacity. The first task was finding some continuous roll paper that would fit, because the official stock for this thing is all labels. He got lucky on the first try and a roll of 2 7/16″ receipt paper fit the bill perfectly.

The printer itself doesn’t have much brains; it prints bitmaps 672 bits wide, and as long as you care to make them. While the initial experiments succeeded in printing graphics, [Eric] needed a way to convert his stories to bitmapped text to send to the printer. The human-readable font file format known as BDF (glyph Bitmap Distribution Format) was a perfect fit, since a library to render it was readily available. On top of that, the open-source tool otf2bdf will convert a TrueType (TTF) font to BDF, completing his font-rendering chain.

[Eric] has these printers working with both Linux and windows, either one running on a PC where his software resides, and has it all well-documented on his site. With this in place, it’s simply a matter of coming up with the stories to print. We think it would be perfect for Hackaday dailies!

We’ve seen interesting hacks with disused printers before, like this ascii-art generating cartridge.