It’s a piece of common knowledge, that MS-DOS wasn’t capable of multitasking. For that, the Microsoft-based PC user would have to wait for the 80386, and usable versions of Windows. But like so many such pieces of received Opinion, this one is full of holes. As [Lunduke] investigates, there were several ways to multitask DOS, and they didn’t all depend on third-party software.

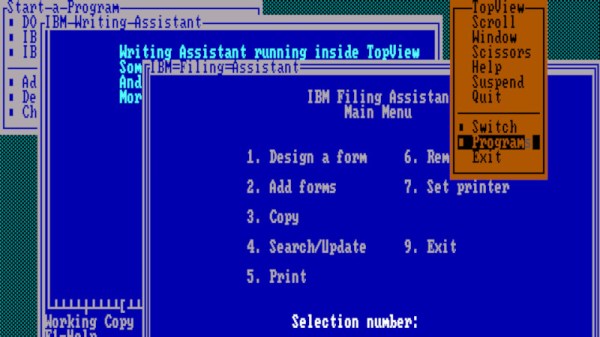

A quick look at DESQview and Concurrent DOS was expected from this article, but of more surprise is that IBM had a multitasking DOS called TopView, or even that Microsoft themselves released the fully multitasking MS-DOS 4.0. We remember DOS 4 as being less than sparkling, but reading the article it’s obvious that we’re thinking of the single-tasking version 4.01.

From 2023 it seems obvious that multitasking is a fundamental requirement of PC use, but surprisingly back in the 1980s a PC was much more a single-application device. On one hand it’s surprising given the number of multitasking DOS products on the market that none of them became mainstream, but perhaps the best evidence of the PC market simply not being ready for it comes in the fact that they didn’t.

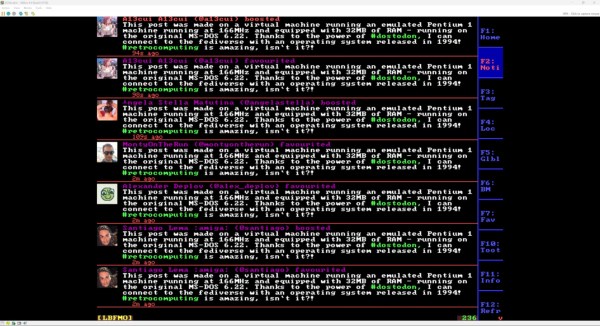

If you fancy experimenting with DOS multitasking, at least machines on which to do it can still be found.