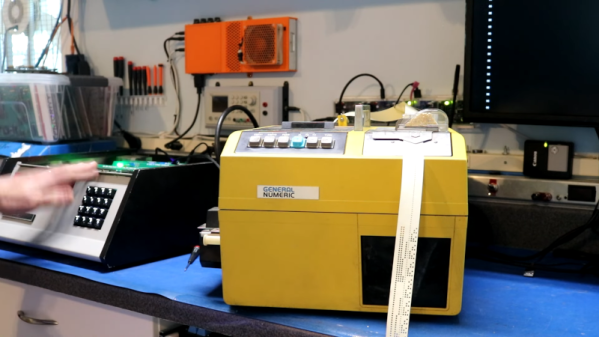

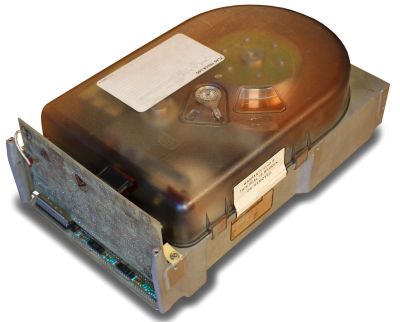

As part of the eternal quest within the realm of retrocomputing, storage devices can be one of the most challenging, especially when it comes to firmly obsolete hard drives, such as the CDC Finch drive. This compact 8″ HDD replaced the previous 14″ models with a form factor that was decidedly more portable. These Finch drives being 1980s technology that got run pretty hard before their retirement, it’s little wonder that they’d end up on the repair bench over at [Usagi Electric]

Introduced in the early 1980s, the CDC Model 9410 Finch drive was unlike its 14″ predecessors in that it is a sealed unit, with maintenance-free air filtration. With the 14″ models you’d have both fixed and swappable platters, with far less consideration for dust exposure. This makes these Finch drives more touchy to work on, not unlike HDDs today, and adds to the excitement when repairing one of these old drives.

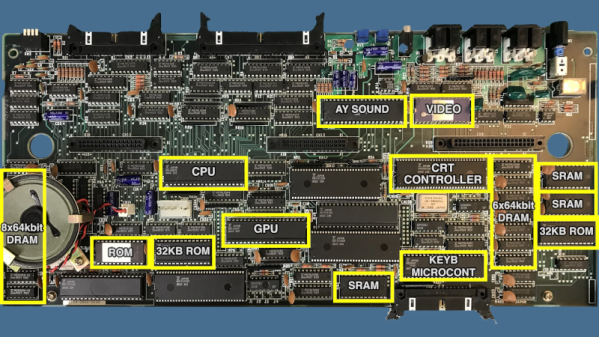

In this video, two differently broken Finch drives are discussed. Both appear to have an issue on the controller board, with one not responding to communications on the interface, while the other featuring a dead short on the interface pins. The first drive was brought back to life by replacing a dead SN75110 line driver IC, as well as a dead 7818 voltage regulator that was only outputting a sad 0.3 V.

Unfortunately, after half an hour of uptime and in the process of dumping data the drive errored out with a Not Ready, indicating that there are further issues on the controller board to fix. The good news here is that the platters appear to be pretty robust, but the controller boards on these old drives tend to develop issues over the years, something which will be further explored in upcoming videos.

Continue reading “Reviving An 8-Inch Hard Drive From The 1980s”