You’ve likely heard of Nitinol wire before, but we suspect the common base knowledge doesn’t go much beyond repeating that it’s a shape-memory alloy. [Bill Hammack], the Engineer Guy, takes us on a quick journey of all the cool stuff there is to know about Nitinol and shape-memory alloys.

The name itself is like saying Kleenex when you mean tissue, or using the V-word when you mean hook and loop fasteners. The first few letters of Nickel Titanium Naval Ordnance Laboratories combine to form the name of what is essentially a nickel-titanium alloy developed in 1962: Nitinol. It’s called shape-memory because you can stretch or bend it at room temperature and it will return to the original shape when heated at around 75 C (167 F). This particular metal can do that because its bonds form a “twinned structure” of rhombus shapes — bending or stretching moves those rhombuses (or rhombi, take your pick) but doesn’t change which atoms are bonded to one another.

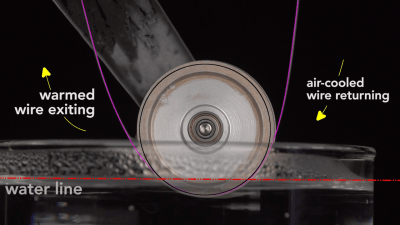

Has this material science excursion bored you to tears yet? That’s why we love [Bill’s] work. He has always done a fantastic job of demystifying common mysticism and this is no different. The video below does a much better job of illustrating what we’ve described above, but also pull out a Nitinol engine for added wow-factor. A straight piece of Nitinol is bent into a loop around two pulleys. The lower pulley is submerged in hot water, causing the Nitinol to want to straighten out, but it loops back to the top pulley, bending and cooling in the air and creating a lever effect that drives the engine. We saw a more complex version of this concept last year.

Has this material science excursion bored you to tears yet? That’s why we love [Bill’s] work. He has always done a fantastic job of demystifying common mysticism and this is no different. The video below does a much better job of illustrating what we’ve described above, but also pull out a Nitinol engine for added wow-factor. A straight piece of Nitinol is bent into a loop around two pulleys. The lower pulley is submerged in hot water, causing the Nitinol to want to straighten out, but it loops back to the top pulley, bending and cooling in the air and creating a lever effect that drives the engine. We saw a more complex version of this concept last year.

You know those eyeglass frames you can bend in any way and they’ll pop back to the original shape? They’re taking advantage of the super-elasticity of Nitinol. [Bill] also recounts uses as stents for medical applications, and oddball engineering tricks in the automotive industry.

It’s great to see the Engineer Guy back. Favorites of ours have been the science behind disposable diapers and the aluminum beverage can. More recently he released Faraday’s lecture series, wrote a book on airships, appeared on Outlaw Tech on the Science Channel, and started a family. Thanks for fitting these illustrative videos in when you can [Bill]!

Continue reading “The Metal That Never Forgets: Nitinol And Shape-Memory”