Night vision aficionado [Nicholas C] shared an interesting teardown of a Norwegian SIMRAD GN1 night vision device, and posted plenty of pictures, along with all kinds of background information about their construction, use, and mounting. [Nicholas] had been looking for a night vision device of this design for some time, and his delight in finding one is matched only by the number of pictures and detail he goes into when opening it up.

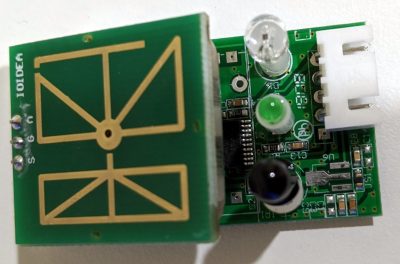

What makes the SIMRAD GN1 an oddball is the fact that it doesn’t look very much like other, better known American night vision devices. Those tend to have more in common with binoculars than with the GN1’s “handheld camera” form factor. The GN1 has two eyepieces in the back and a single objective lens on the front, which is off-center and high up. The result is a seriously retrofuturistic look, which [Nicholas] can’t help but play to when showing off some photos.

[Nicholas] talks a lot about the build and tears it completely down to show off the internal optical layout necessary to pipe incoming light through the image intensifier and bend it around to both eyes. As is typical for military hardware like this, it has rugged design and every part has its function. (A tip: [Nicholas] sometimes refers to “blems”. A blem is short for blemish and refers to minor spots on optics that lead to visual imperfections without affecting function. Blemished optics and intensifier tubes are cheaper to obtain and more common on the secondary market.)

In wrapping up, [Nicholas] talks a bit about how a device like this is compatible with using sights on a firearm. In short, it’s difficult at best because there’s a clunky thing in between one’s eyeballs and the firearm’s sights, but it’s made somewhat easier by the fact that the GN1 can be mounted upside down without affecting how it works.

Night vision in general is pretty cool stuff and of course DIY projects abound, like the OpenScope project which leverages digital cameras and 3D printing, as well as doing it the high-voltage image intensifier tube way.

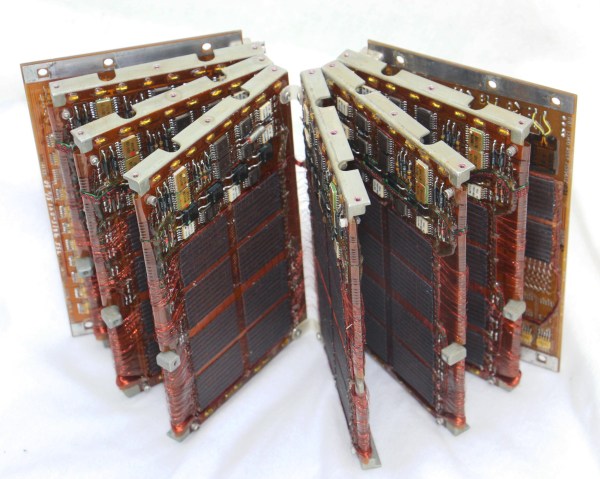

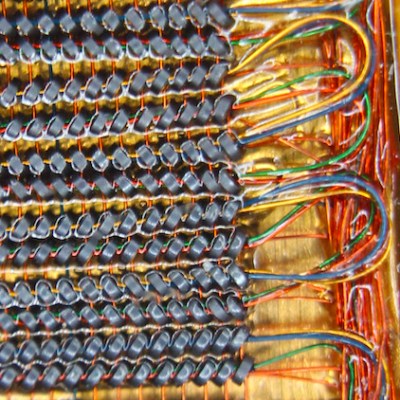

Amazingly these computers were composed of all digital logic, no centralized controller chip in this baby. That explains the need for the seven circuit boards which host a legion of logic chips, all slotting into a backplane.

Amazingly these computers were composed of all digital logic, no centralized controller chip in this baby. That explains the need for the seven circuit boards which host a legion of logic chips, all slotting into a backplane.