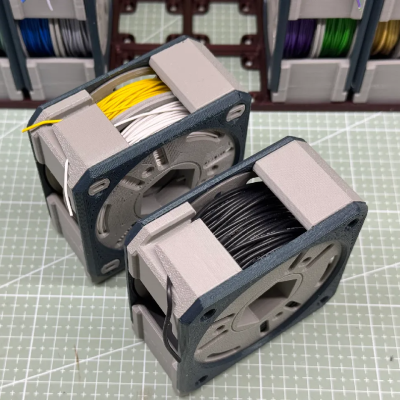

Hardware hackers tend to have loads of hookup wire, and that led [firstgizmo] to design a 3D printable wire and cable spool storage system. As a bonus, it’s Gridfinity-compatible!

There are a lot of little design touches we love. For example, we like the little notch into which the wire ends are held, which provides a way to secure the loose ends without any moving parts. Also, while at first glance these holders look like something that goes together with a few screws, they actually require no additional hardware and can be assembled entirely with printed parts. But should one wish to do so, [firstgizmo] has an alternate design that goes together with some M3 bolts instead.

Want to adjust something? The STEP files are included, which we always love to see because it makes modifications to the models so much more accessible. One thing that hasn’t changed over the years is that making engineering-type adjustments to STL files is awful, at best.

If there is one gotcha, it is that one must remove wire from their old spools and re-wind onto the new to use this system. However, [firstgizmo] tries to make that as easy as possible by providing two tools to make re-spooling easier: one for hand-cranking, and one for using a hand drill to do the work for you.

It’s a very thoughtful design, and as mentioned, can also be used with the Gridfinity system, which seems to open organizational floodgates in most people’s minds. Most of us are pinched for storage space, and small improvements in space-saving really, really add up.