Our hats off to [SpeedyCop] and his [Gang of Outlaws] for turning a junked former Vietnam War helicopter into both an amphibious vehicle and a road race car. Yes, that’s right. It’s both driven on water and raced in the 24 Hours of LeMons at New Jersey Motorsports Park.

It started life as a 1969 Bell OH-58 Kiowa (US Army Vietnam Assault helo) and had not only served in Vietnam but also for a federal drug task force. It was chopped up for parts and the body found its way to [SpeedyCop] and friends. The body now sits on an 80s Toyota van chassis, has a Mazda Miata rear suspension, and Audi 3.0 V6 engine.

The pontoons were originally added to hide the seam between the helicopter body and the van but they then inspired the idea of making it amphibious. And with the addition of a four-blade, 7000 RPM propeller from a parasail boat, the idea became reality, as you can see in the video after the break (we suspect the trailing line is a rope to pull it back to shore in case of engine failure).

Continue reading “Vietnam War Helicopter Turned Amphibious Racecar”

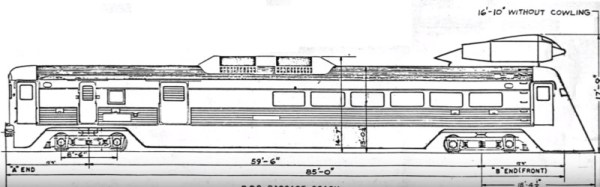

![The front of the Soviet jet train on a monument in Tver, Russia. By Eskimozzz [PD], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/576px-d181d182d0b5d0bbd0b0.jpg?w=300)