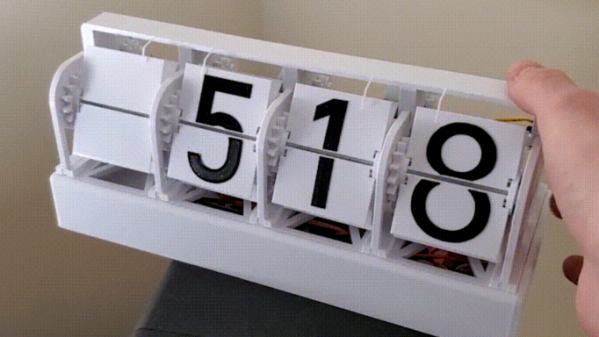

Seven-segment displays have been around for a long time, and there is a seemingly endless number of ways to build them. The latest of is a mechanical seven-segment from a master of 3D printed mechanisms, [gzumwalt], and can use a single motor to cycle through all ten possible numbers.

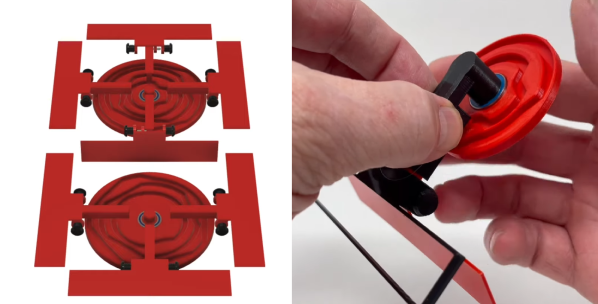

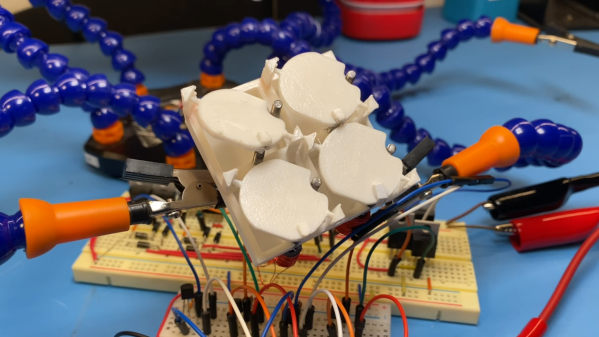

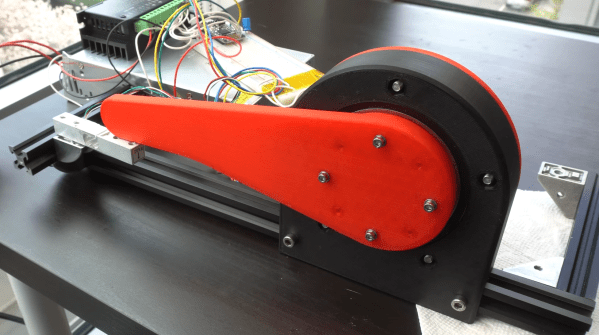

The trick lies in a synchronized pair of rotating discs, one for the top four segments and another for the bottom three segments. Each disc has a series of concentric cam slots to drive followers that flip the red segments in and out of view. The display can cycle through all ten states in a single rotation of the discs, so the cam paths are divided in 36° increments. [gzumwalt] has shown us a completed physical version, but judging by CAD design and working prototype of a single segment, we are pretty confident it will. While it’s not shown in the design, we suspect it will be driven by a stepper motors and synchronized with a belt or intermediate gear.

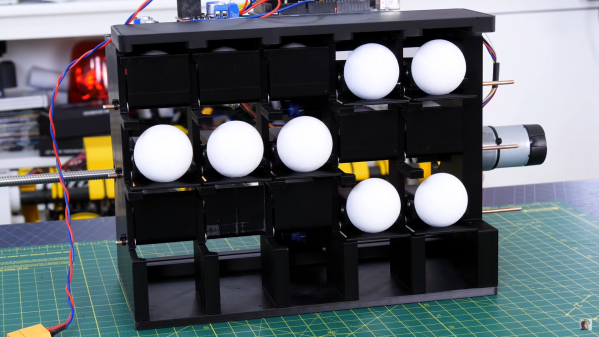

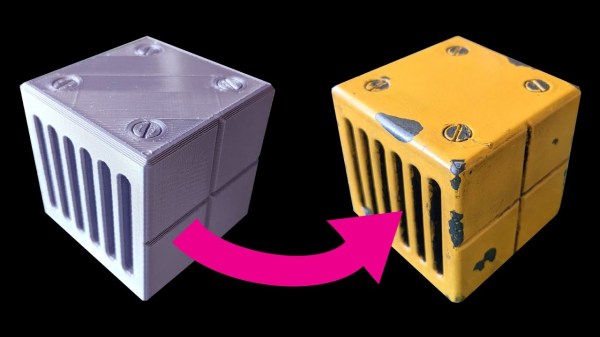

Another 3D printed mechanical display we’ve seen recently is a DIY flip dot, array, which uses the same electromagnet system as the commercial versions. [gzumwalt] has a gift for designing fascinating mechanical automatons around a single motor, including an edge avoiding robot and a magnetic fridge crawler.

Continue reading “Mechanical 7-Segment Display Uses A Single Motor”