Back in 1968, a book titled “How to Build a Working Digital Computer” claimed that the sufficiently dedicated reader could assemble their own functioning computer at home using easily obtainable components. Most notably, the design utilized many elements that were fashioned from bent paperclips. It’s unclear how many readers actually assembled one of these so-called “Paperclip Computers”, but today we’re happy to report that [Mike Gardi] has completed his interpretation of the 50+ year old homebrew computer.

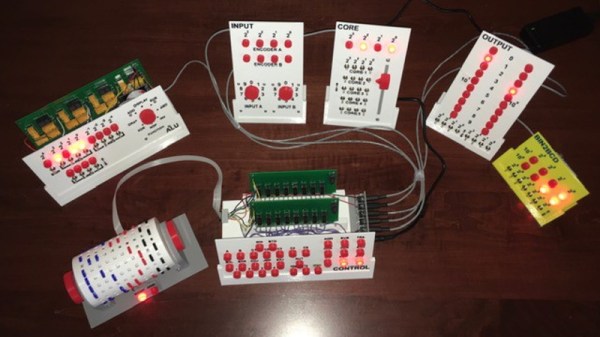

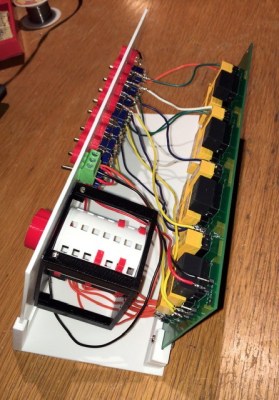

The purist might be disappointed to see how far [Mike] has strayed from the original, but we see his embrace of modern construction techniques as a necessary upgrade. He’s recreated the individual computer components as they were described in the book, but this time plywood and wheat bulbs have given way to 3D printed panels and LEDs. While the details may be different, the end goal is the same: a programmable digital computer on a scale that can be understood by the operator.

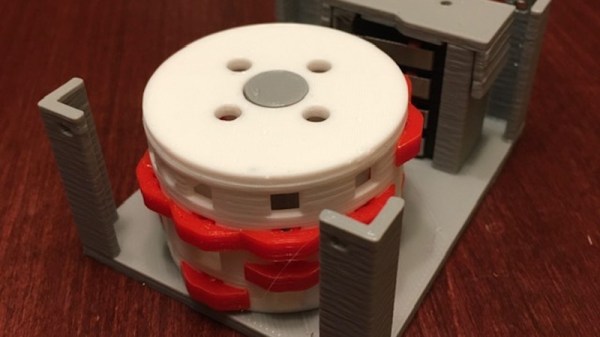

To say that [Mike] did a good job of documenting his build would be an understatement. He’s spent the last several months covering every aspect of the build on Hackaday.io, giving his followers a fantastic look at what goes into a project of this magnitude. He might not have bent many paperclips for his Working Digital Computer (WDC-1), but he certainly designed and fabricated plenty of impressive custom components. We wouldn’t be surprised if some of them, such as the 3D printed slide switch we covered last month, started showing up in other projects.

While the WDC-1 is his latest and certainly greatest triumph, [Mike] is no stranger to recreating early digital computers. We’ve been bringing you word of his impressive replicas for some time now, and each entry has been even more impressive than the last. With the WDC-1 setting the bar so high, we can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.

Continue reading “A Modern Take On The “Paperclip Computer””