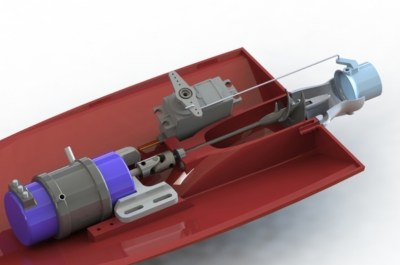

When designing model aircraft of any shape or size, it’s useful to know the performance you can expect from the components chosen. For motors and propellers, this can be difficult. It’s always best to test them in combination. However, with the numbers of propeller and motor combinations possible, such data can be tough to come by. [Nikus] decided it would be easier to just do the testing in-house, and built a rig to do so.

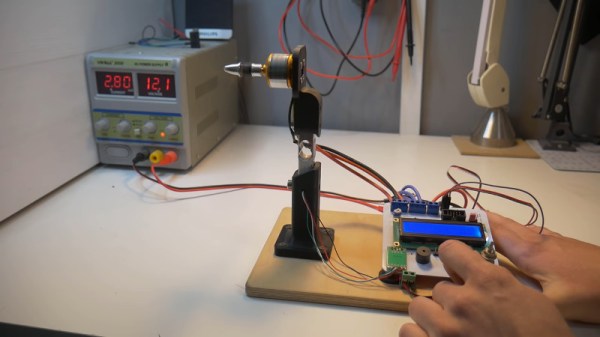

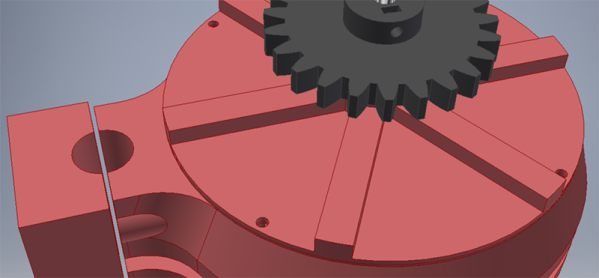

The key component in this build is the strain gauge, which comes already laced up with an Arduino-compatible analog-digital converter module. Sourced for under $10 from Banggood, we can’t help but think that we’ve got it easy in 2018. A sturdy frame secures motor and propeller combination to the strain gauge assembly. An ATMEGA328 handles sending commands to the motor controller, reading the strain gauge results, and spitting out data to the LCD.

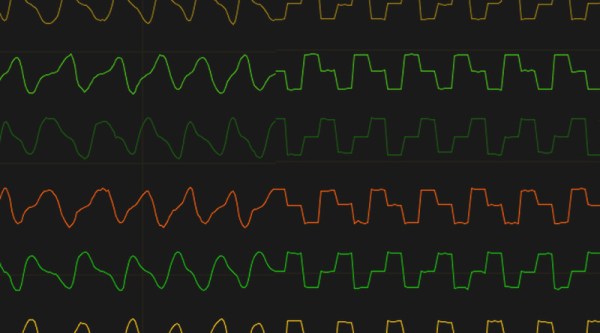

It’s a cheap and effective build that solves a tricky problem and would be a useful addition to the workshop for any serious modeler. We’ve seen other approaches in this area too, for those eager to graph their motor performance data. Video after the break.

[Thanks to Baldpower for the tip!]

Continue reading “Brushless Motor Thrust Stand Provides Useful Data”