These days, surveillance cameras are all around us, and they’re smarter than ever. In particular, many of them are running advanced algorithms to recognize faces and scan license plates, compiling ever-greater databases on the movements and lives of individuals. Flock You is a project that aims to, at the very least, catalogue this part of the surveillance state, by detecting these cameras out in the wild.

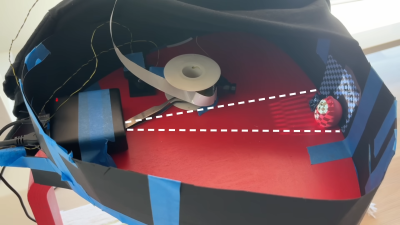

The system is most specifically set up to detect surveillance cameras from Flock Safety, though it’s worth noting a wide range of companies produce plate-reading cameras and associated surveillance systems these days. The device uses an ESP32 microcontroller to detect these devices, relying on the in-built wireless hardware to do the job. The project can be built on a Oui-Spy device from Colonel Panic, or just by using a standard Xiao ESP32 S3 if so desired. By looking at Wi-Fi probe requests and beacon frames, as well as Bluetooth advertisements, it’s possible for the device to pick up telltale transmissions from a range of these cameras, with various pattern-matching techniques and MAC addresses used to filter results in this regard. When the device finds a camera, it sounds a buzzer notifying the user of this fact.

Meanwhile, if you’re interested in just how prevalent plate-reading cameras really are, you might also find deflock.me interesting. It’s a map of ALPR camera locations all over the world, and you can submit your own findings if so desired. The techniques used by in the Flock You project are based on learnings from the DeFlock project. Meanwhile, if you want to join the surveillance state on your own terms, you can always build your own license plate reader instead!

[Thanks to Eric for the tip!]