Bismuth is known for a few things: its low melting point, high density, and psychedelic hopper crystals. A literal deep-dive into any molten metal would be a terrible idea, regardless of low melting point, but [Electron Impressions]’s video on “Why Do Bismuth Crystals Look Like That” may be the most educational eight minutes posted to YouTube in the past week.

The whole video is worth a watch, but since spoilers are the point of these articles, we’ll let you in on the secret: it all comes down to Free Energy. No, not the perpetual motion scam sort of free energy, but the potential that is minimized in any chemical reaction. There’s potential energy to be had in crystal formation, after all, and nature is always (to the extent possible) going to minimize the amount left on the table.

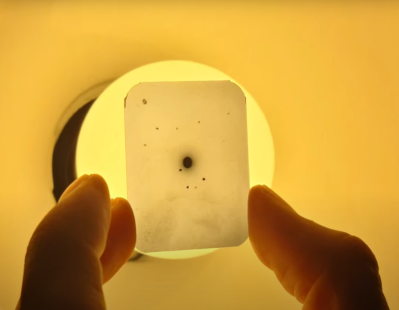

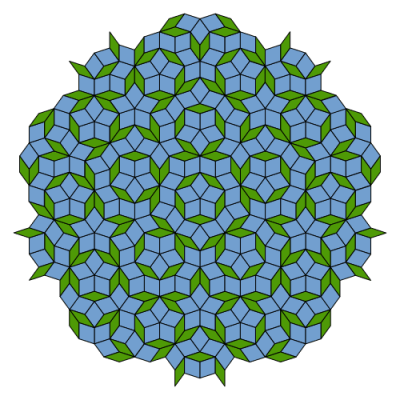

In bismuth crystals– at least when you have a pot slowly cooling at standard temperature and pressure–that means instead of a large version of the rhombahedral crystal you might naively expect if you’ve tried growing salt or sugar crystals in beakers, you get the madman’s maze that actually emerges. The reason for this is that atoms are preferentially deposited onto the vertexes and edges of the growing crystal rather than the face. That tends to lead to more vertexes and edges until you get the fractal spirals that a good bismuth crystal is known for. (It’s not unlike the mechanism by which the dreaded tin whiskers grow, as a matter of fact.)

Bismuth isn’t actually special in this respect; indeed, nothing in this video would not apply to other metals, in the right conditions. It just so happens that “the right conditions” in terms of crystal growth and the cooling of the melt are trivial to achieve when melting Bismuth in a way that they aren’t when melting, say, Aluminum in the back yard. [Electron Impressions] doesn’t mention because he is laser-focused on Bismuth here, but hopper crystals of everything from table salt to gold have been produced in the lab. When cooling goes to quick, it’s “any port in a storm” and atoms slam into solid phase without a care for the crystal structure, and you get fine-grained, polycrystaline solids; when it goes slowly enough, the underlying crystal geometry can dominate. Hopper crystals exist in a weird and delightful middle ground that’s totally worth eight minutes to learn about.

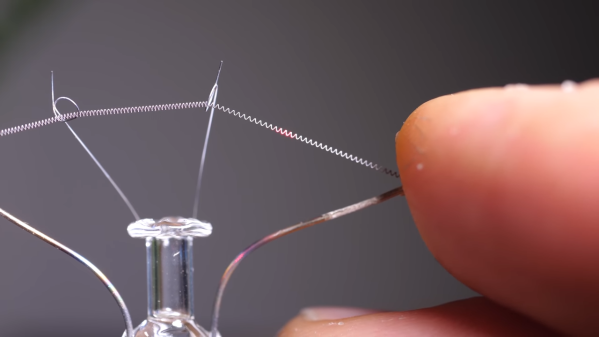

Aside from being easy to grow into delightful crystals, bismuth can also be useful when desoldering, and, oddly enough, making the world’s fastest transistor.