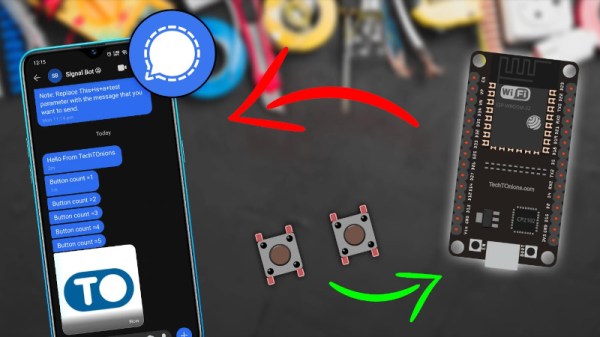

After an electronic IoT device has been deployed into the world, it may be necessary to reprogram or update it. But if physical access to the device (or devices) is troublesome or no longer possible, that’s a problem.

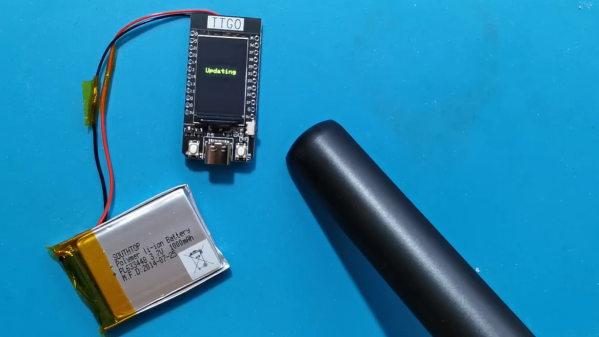

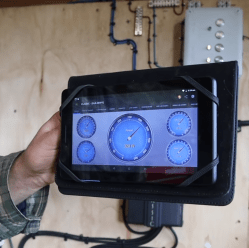

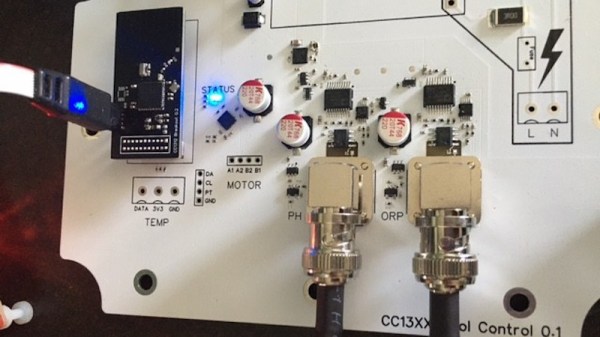

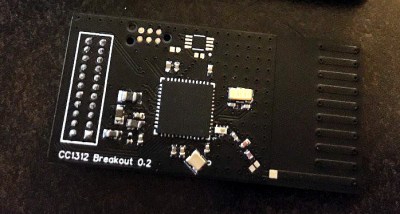

Fortunately, over-the-air (OTA) firmware updates are a thing, allowing embedded devices to be reprogrammed over their wireless data connection instead of with a physical hardware device. Security is of course a concern, and thankfully [Refik] explains how to set up a basic framework so that ESP32 OTA updates can happen securely, allowing one to deploy devices and still push OTA updates in confidence.

[Refik] begins by setting up a web server using Ubuntu Linux, and sets up HTTPS using a free SSL certificate from Let’s Encrypt, but a self-signed SSL certificate is also an option. Once that is done, the necessary fundamentals are in place to support deploying OTA updates in a secure manner. A bit more configuration, and the rest is up to the IoT devices themselves. [Refik] explains how to set things up using the esp32FOTA library, but we’ve also seen other ways to make OTA simple to use.

You can watch a simple secure OTA firmware update happen in the video, embedded below. There are a lot of different pieces working together, so [Refik] also provides a second video for those viewers who prefer a walkthrough to help make everything clear. Watch them both, after the break.

Continue reading “How To Easily Set Up Secure OTA Firmware Updates On ESP32”