Much to the chagrin of many living in North America who still need to do things like keep two sets of wrenches on hand, most of the rest of the world has standardized to a simpler measurement system using metric units exclusively. The metric system is widely adopted worldwide, but we still use a base-60 system for timekeeping that predates the rest of the metric system. The French did attempt to “decimalize” timekeeping as well with the French Republican Calendar at around this same time, but this “metric” timekeeping system never caught on particularly well. It’s still an interesting historical tidbit, and [ClassTech] built this modern metric clock to explore it a little more.

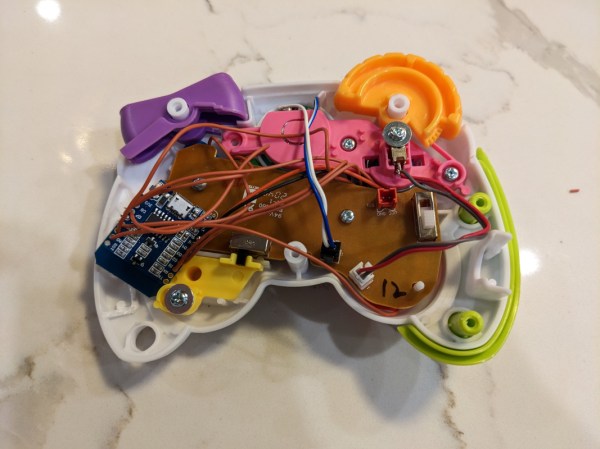

The system itself uses ten-day weeks, ten-hour days, and 100-minute hours which makes it more in line with the base-10 system common to the rest of the metric system. But this means that a second in the French Republican system actually works out to a little less than one and a half SI seconds, meaning that a modern timekeeping computer needs to do a little more math to display the correct time at the correct interval. [ClassTech] is using a Particle Photon IoT processor getting the time from a NTP server, converting it to “metric time”, and displaying the time on a Nextion touch display.

While the device is reported to update the time once per second, we’re not sure if this is every SI second or every French Republican second. Either way, there are plenty of reasons this timekeeping system never gained widespread adoption, and a surprising one is that timekeeping tends to be easier in a base-60 system due to its capability of having more divisors. Many other reasons are less technical and more cultural, and timekeeping tends to be surprisingly difficult to coordinate even among shared numbers systems and languages.