[Tom], of the YouTube channel ThingsTomLike, found a very sweet little mechanical Pong clone at a thrift store. It came in broken, but in only fifteen minutes of your time, [Tom] manages a complete teardown and repair. (Video, embedded below.)

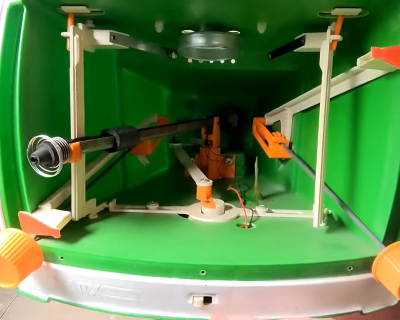

The game works by balancing a lightbulb on the end of a pivot arm that projects a “ball” onto a screen, while players move their paddles up and down to hit the spring that surrounds the light assembly. The ball arm gets periodically kicked by a DC motor and cam assembly, which makes it careen wildly back and forth across the screen.

The game works by balancing a lightbulb on the end of a pivot arm that projects a “ball” onto a screen, while players move their paddles up and down to hit the spring that surrounds the light assembly. The ball arm gets periodically kicked by a DC motor and cam assembly, which makes it careen wildly back and forth across the screen.

It’s a marvel of simple, no-IC engineering. Ironically, it might have been cheaper than making it out of silicon at the time, but viewed from today’s economy, just the human labor in adjusting that counterweight so that the “ball” floats would blow the budget.

Why a screen and lightbulb? Because it’s emulating Pong, a video game, the new kid on the block. But even 45 years later, we think it has got a charm all of its own that the cold digital logic of Pong lacks, even if the gameplay suffers.