Some cool-mist humidifiers work by flinging water at a vaporizer, but our favorite kind uses a piezoelectric transducer. These work by using high-frequency sound waves to pound the surface of the water with mechanical energy. That energy introduces standing waves that force the water to break apart into a fine mist on the surface of the piezo disk.

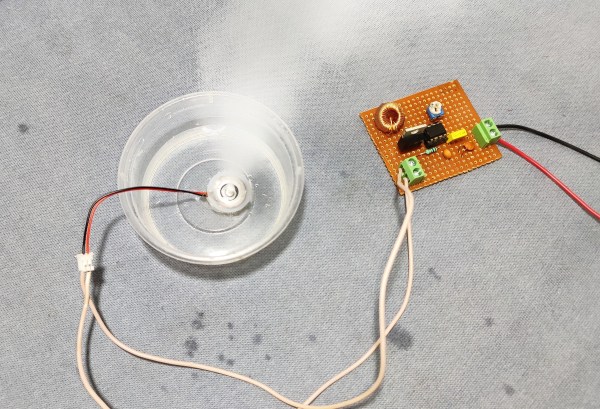

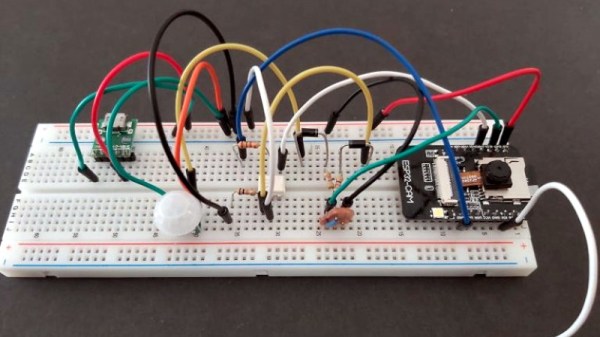

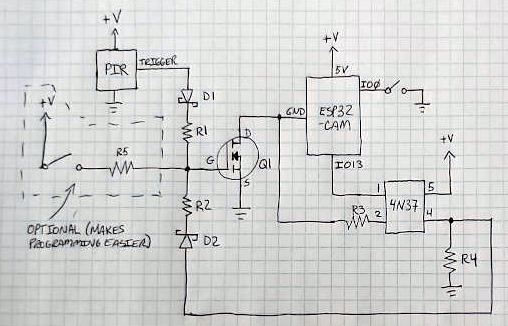

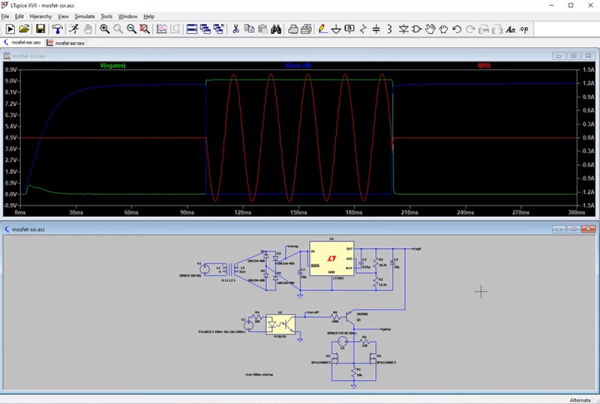

The driving circuit for this DIY mist maker uses a 555 to generate 113 KHz, a trimmer potentiometer to fine-tune it, and a MOSFET to amplify the signal. You don’t need much more than that and a handful of passives to recreate this cool junk box experiment, but the spec of the piezo disk is quite important. The circuit is designed for atomizing transducers, which have a resonant frequency of 113 KHz — much higher than your average junk box piezo. Check out the demo and build video after the break.

Atomizing transducers can do way more than than moisten the air for our comfort. They’re not picky about where the water comes from, so if you have enough of them, you can dry a load of laundry in a few minutes.

Continue reading “Cool Off With A Piezo And A Glass Of Water”