[Sam] took an information security class at Oklahoma State University back in 2013. For his final project, he and a team of other students had to find a security vulnerability and then devise a theoretical plan to exploit it. [Sam’s] team decided to focus on the school’s ID cards. OSU’s ID cards are very similar to credit cards. They are the same size and shape, they have data encoded on a magnetic strip, and they have a 16 digit identification number. These cards were used for several different purposes. Examples include photo ID, physical access to some areas on campus, charges to an online account, and more.

[Sam] and his team analyzed over 100 different cards in order to get a good sample. They found that all cards started with same eight digits. This is similar to the issuer identification number found in the first six digits of a credit card number. Th analysis also showed that there were only three combinations used for the next two digits. Those were either 05, 06, or 11. With that in mind, the total possible number of combinations for card numbers was mathematically calculated to be three million.

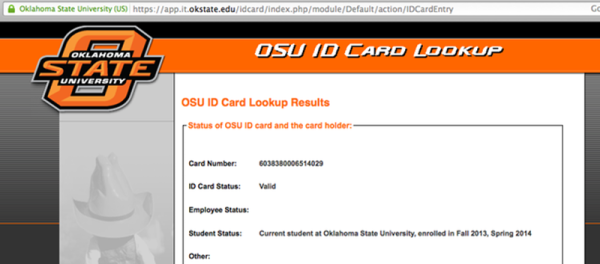

OSU also had a URL printed on the back of each card. This website had a simple form with a single field. The user can enter in a 16 digit card number and the system would tell the user if that card was valid. The page would also tell you if the card holder was an employee, a student, or if there were any other special flags on the card. We’re not sure why every student would need access to this website, but the fact is that the URL was printed right on the back of the card. The website also had no limit to how many times a query could be made. The only hint that the university was aware of possible security implications was the disclaimer on the site. The disclaimer mentioned that usage of the tool was “logged and tracked”.

The next step was to purchase a magnetic card reader and writer. The team decoded all of the cards and analyzed the data. They found that each card held an expiration date, but the expiration date was identical for every single card. The team used the reader/writer to copy the data from [Sam’s] card and modify the name. They then wrote the data back onto a new, blank magnetic card. This card had no printing or markings on it. [Sam] took the card and was able to use it to purchase items from a store on campus. He noticed that the register reached back to a server somewhere to verify his real name. It didn’t do any checks against the name written onto the magstripe. Even still, the cashier still accepted a card with no official markings.

The final step was to write a node.js script to scrape the number verification website. With just 15 lines of code, the script will run through all possible combinations of numbers in a random sequence and log the result. The website can handle between three and five requests per second, which means that brute forcing all possible combinations can be completed in roughly two days. These harvested numbers can then be written onto blank cards and potentially used to purchase goods on another student’s account.

[Sam’s] team offers several recommendations to improve the security of this system. One idea is to include a second form of authorization, such as a PIN. The PIN wouldn’t be stored on the card, and therefore can’t be copied in this manner. The primary recommendation was to take down the verification website. So far OSU has responded by taking the website offline, but no other changes have been made.

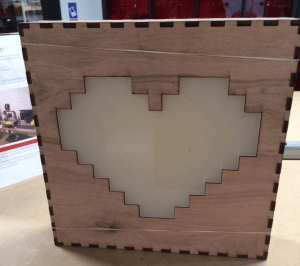

She started out by designing the enclosure. Having access to a laser cutter, she opted to make it out of thin plywood. [Stacey] used an online tool called

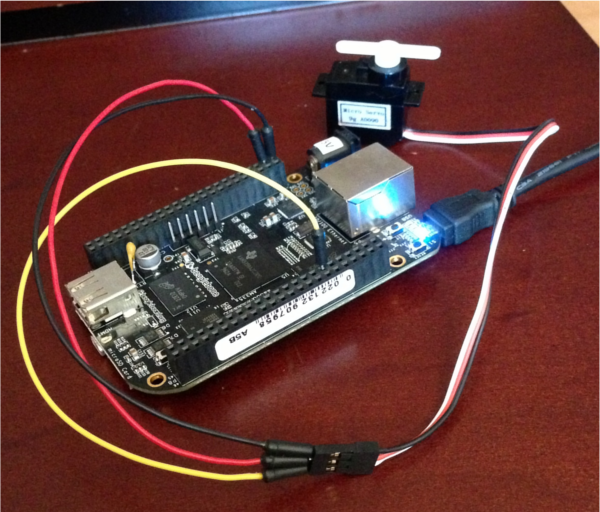

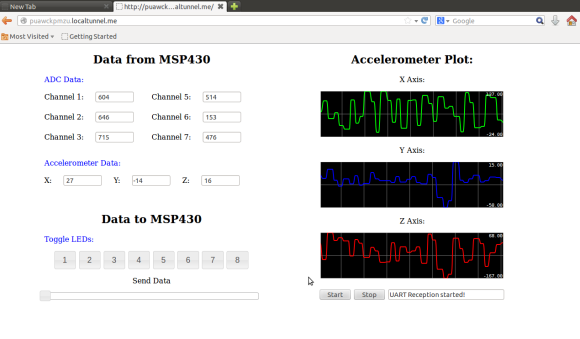

She started out by designing the enclosure. Having access to a laser cutter, she opted to make it out of thin plywood. [Stacey] used an online tool called  The Internet of Things is here in full force. The first step when adding to the Internet of Things is obvious, adding a web interface to your project. [Jaspreet] wrote in to tell us about his project that adds a

The Internet of Things is here in full force. The first step when adding to the Internet of Things is obvious, adding a web interface to your project. [Jaspreet] wrote in to tell us about his project that adds a