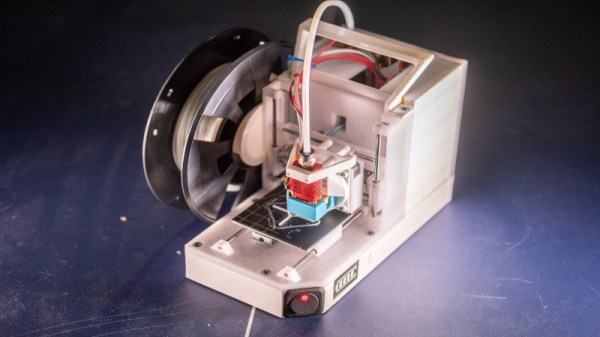

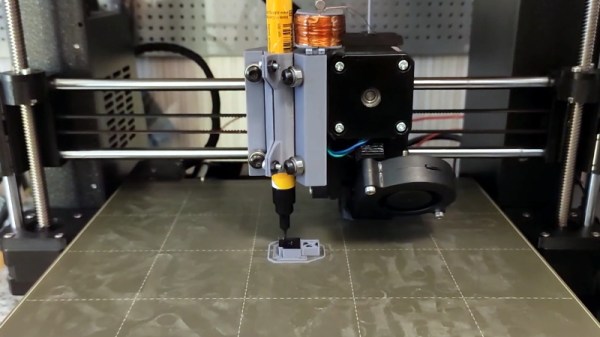

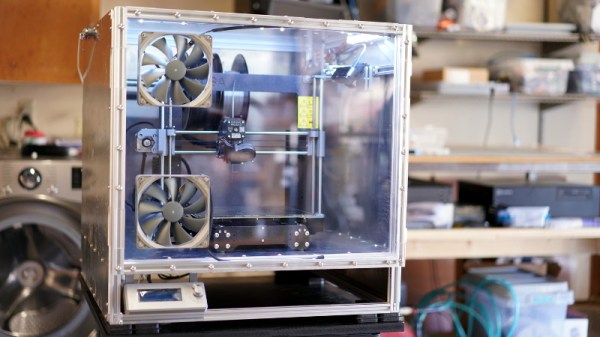

When we think 3D printers, we most commonly think of the fused-deposition modelling type that squirts molten plastic out of a hot nozzle. Typically, these are tabletop units designed to be set up and used in a workshop environment. [BingoFishy] dared to think outside the box however, and whipped up a compact, portable 3D printer for working out on the road.

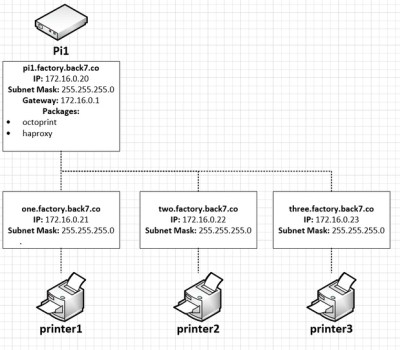

The printer is almost entirely self-contained, running an OctoPrint controller with built-in hotspot which allows print files to be sent to the unit over a smartphone. The motion platform is built out of DVD drive stepper motors and rails, with dual motors used on the Z-axis to ensure there’s enough torque to move smoothly. Power is courtesy of 26650 cells, in a 2S3P configuration, which provides 3 hours of runtime. While this might not sound like much, for a compact printer with a small build volume, it’s a useful period of time to work with.

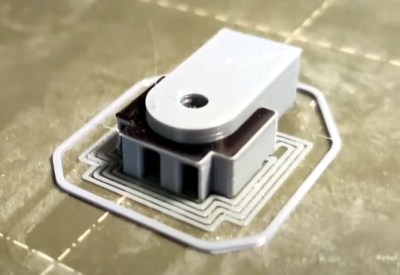

While such a build will never replace a solid desktop unit with a large build volume, it nevertheless could come in handy for producing small parts out in the field. We can imagine a college robotics team toting one of these to a regional contest, where it could prove invaluable for whipping up some bushings after something breaks unexpectedly. The finish of the project is great, too, though we’ve seen great results from less-polished builds in the past as well. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Portable Printer Is A Top Notch High School Project”