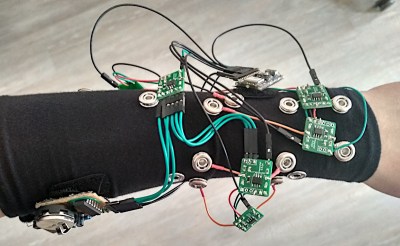

We don’t see many EMG (electromyography) projects, despite how cool the applications can be. This may be because of technical difficulties with seeing the tiny muscular electrical signals amongst the noise, it could be the difficulty of interpreting any signal you do find. Regardless, [hut] has been striving forwards with a stream of prototypes, culminating in the aptly named ‘Prototype 8’

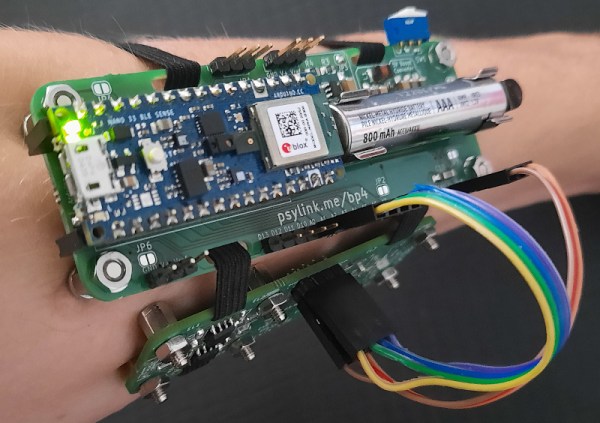

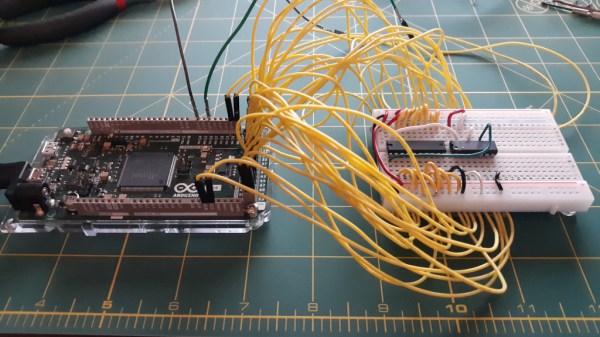

The current prototype uses a main power board hosting an Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense, as well as a boost converter to pump up the AAA battery to provide 5 volts for the Arduino and a selection of connected EMG amplifier units. The EMG sensor is based around the INA128 instrumentation amplifier, in a pretty straightforward configuration. The EMG samples along with data from the IMU on the Nano 33 BLE Sense, are passed along to a connected PC via Bluetooth, running the PsyLink software stack. This is based on Python, using the BLE-GATT library for BT comms, PynPut handing the PC input devices (to emit keyboard and mouse events) and tensorflow for the machine learning side of things. The idea is to use machine learning from the EMG data to associate with a specific user interface event (such as a keypress) and with a little training, be able to play games on the PC with just hand/arm gestures. IMU data are used to augment this, but in this demo, that’s not totally clear.

All hardware and software can be found on the project codeberg page, which did make us double-take as to why GnuRadio was being used, but thinking about it, it’s really good for signal processing and visualization. What a good idea!

Obviously there are many other use cases for such a EMG controlled input device, but who doesn’t want to play Mario Kart, you know, for science?

Checkout the demo video (embedded below) and you can see for yourself, just be aware that this is streaming from peertube, so the video might be a little choppy depending on your local peers. Finally, if Mastodon is your cup of tea, here’s the link for that. Earlier projects have attempted to dip into EMG before, like this Bioamp board from Upside Down Labs. Also we dug out an earlier tutorial on the subject by our own [Bil Herd.]

Continue reading “PsyLink An Open Source Neural Interface For Non-Invasive EMG”

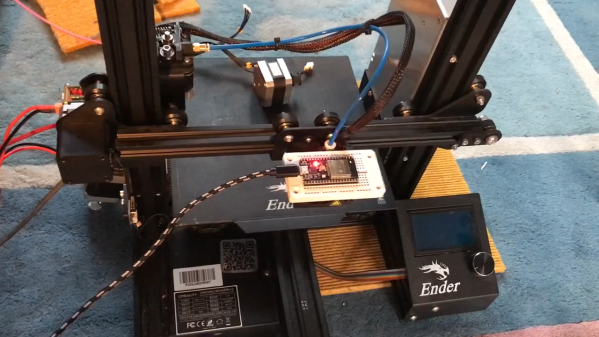

Granted, based as it is on the gantry of an old 3D printer, [Neumi]’s WiFi scanner has a somewhat limited work envelope. A NodeMCU ESP32 module rides where the printer’s extruder normally resides, and scans through a series of points one centimeter apart. A received signal strength indicator (RSSI) reading is taken from the NodeMCU’s WiFi at each point, and the position and RSSI data for each point are saved to a CSV file. A couple of Python programs then digest the raw data to produce both 2D and 3D scans. The 3D scans are the most revealing — you can actually see a 12.5-cm spacing of signal strength, which corresponds to the wavelength of 2.4-GHz WiFi. The video below shows the data capture process and some of the visualizations.

Granted, based as it is on the gantry of an old 3D printer, [Neumi]’s WiFi scanner has a somewhat limited work envelope. A NodeMCU ESP32 module rides where the printer’s extruder normally resides, and scans through a series of points one centimeter apart. A received signal strength indicator (RSSI) reading is taken from the NodeMCU’s WiFi at each point, and the position and RSSI data for each point are saved to a CSV file. A couple of Python programs then digest the raw data to produce both 2D and 3D scans. The 3D scans are the most revealing — you can actually see a 12.5-cm spacing of signal strength, which corresponds to the wavelength of 2.4-GHz WiFi. The video below shows the data capture process and some of the visualizations.