When someone offers to write you a check for $5 billion for your company, it seems like a good idea to take it. But in the world of corporate acquisitions and mergers, that’s not always the case, as Altium proved this week when they rebuffed a A$38.50 per share offer from Autodesk. Altium Ltd., the Australian company whose flagship Altium Designer suite is used by PCB and electronic designers around the world, said that the Autodesk offer “significantly undervalues” Altium, despite the fact that it represents a 42% premium of the company’s share price at the end of last week. Altium’s rejection doesn’t close the door on ha deal with Autodesk, or any other comers who present a better offer, which means that whatever happens, changes are likely in the EDA world soon.

There were reports this week of a massive explosion and fire at a Chinese polysilicon plant — sort of. A number of cell phone videos have popped up on YouTube and elsewhere that purport to show the dramatic events unfolding at a plant in Xinjiang province, with one trade publication for the photovoltaic industry reporting that it happened at the Hoshine Silicon “997 siloxane” packing facility. They further reported that the fire was brought under control after about ten hours of effort by firefighters, and that the cause is under investigation. The odd thing is that we can’t find a single mention of the incident in any of the mainstream media outlets, even five full days after it purportedly happened. We’d have figured the media would have been all over this, and linking it to the ongoing semiconductor shortage, perhaps erroneously since the damage appears to be limited to organic silicone production as opposed to metallic silicon. But the company does supply something like 17% of the world’s supply of silicon metal, so anything that could potentially disrupt that should be pretty big news.

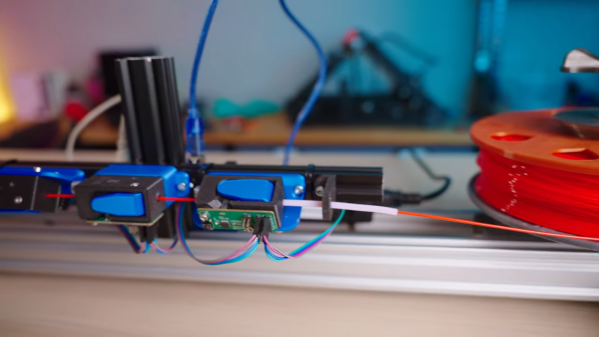

It’s always fun to see “one of our own” take a project from idea to product, and we like to celebrate such successes when they come along. And so it was great to see the battery-free bicycle tire pressure sensor that Hackaday.io user CaptMcAllister has been working on make it to the crowdfunding stage. The sensor is dubbed the PSIcle, and it attaches directly to the valve stem on a bike tire. The 5-gram sensor has an NFC chip, a MEMS pressure sensor, and a loop antenna. The neat thing about this is the injection molding process, which basically pots the electronics in EDPM while leaving a cavity for the air to reach the sensor. The whole thing is powered by the NFC radio in a smartphone, so you just hold your phone up to the sensor to get a reading. Check out the Kickstarter for more details, and congratulations to CaptMcAllister!

We’re saddened to learn of the passing of Dale Heatherington last week. While the name might not ring a bell, the name of his business partner Dennis Hayes probably does, as together they founded Hayes Microcomputer Products, makers of the world’s first modems specifically for the personal computer market. Dale was the technical guru of the partnership, and it’s said that he’s the one who came up with the famous “AT-command set”. Heatherington only stayed with Hayes for seven years or so before taking his a $20 million share of the company and retiring, which of course meant more time and resources to devote to tinkering with everything from ham radio to battle bots. ATH0, Dale.