For how crucial whales have been for humanity, from their harvest for meat and oil to their future use of saving the world from a space probe, humans knew very little about them until surprisingly recently. Most people, even in Herman Melville’s time, considered whales to be fish, and it wasn’t until humans went looking for submarines in the mid-1900s that we started to understand the complexities of their songs. And you don’t have to be a submarine pilot to listen now, either; all you need is something like these homemade hydraphones.

underwater51 Articles

Watertight And Wireless In One Go: The DIY Sea Scooter

To every gadget, tool, or toy, you can reasonably think: ‘Sure I could buy this… but can I make it myself?’ And that’s where [Ben] decided he could, and got to work. On a sea scooter, to be exact.

This sea scooter was to be a fully waterproof, hermetically sealed 3D-printed underwater personal propulsion device, with the extreme constraint that the entire hull and mechanical interfaces are printed in one go. No post-printing holes for shafts, connectors, or seals. It also meant [Ben] needed to embed all electronics, motor, magnetic gearbox, custom battery pack, wireless charging, and non-contact magnetic control system inside the print during the actual print process.

As [Ben] explains, both Bluetooth and WiFi ranges are laughable once underwater. He elegantly solves this with a reed-switch-based magnetic control system. The non-contact magnetic drive avoids shaft penetrations entirely. Power comes from a custom 8S LiFePO₄ pack, charged wirelessly through the hull. Lastly, everything’s wrapped in epoxy to make it as watertight as a real submarine.

The whole trick of ‘print-in-place’ is that [Ben] pauses the builder mid-print, and drops in each subsystem like a secret ingredient. Continuing, he tweaks the printer’s Z-offset, and onwards it goes. It’s tense, high-stakes work; a 14-hour print where one nozzle crash means binning hundreds of dollars’ worth of embedded components.

Still, [Ben] took the chance, and delivered a cool, fully packed and fully working sea scooter. Comment below to discuss the possibilities of building one yourself.

Continue reading “Watertight And Wireless In One Go: The DIY Sea Scooter”

Student Drone Flies, Submerges

Admit it. You’d get through boring classes in school by daydreaming of cool things you’d like to build. If you were like us, some of them were practical, but some of them were flights of fancy. Did you ever think of an airplane that could dive under the water? We did. So did some students at Aalborg University. The difference is they built theirs. Watch it do its thing in the video below.

As far as we can tell, the drone utilizes variable-pitch props to generate lift in the air and downward thrust in water. In addition to the direction of the thrust, water operations require a lower pitch to minimize drag. We’d be interested in seeing how it is all waterproofed, and we’re unsure how deep the device can go. No word on battery life either. From the video, we aren’t sure how maneuverable it is while submerged, but it does seem to have some control. It wouldn’t be hard to add a lateral thruster to improve underwater operations.

This isn’t the first vehicle of its kind (discounting fictional versions). Researchers at Rutgers created something similar in 2015, and we’ve seen other demonstrations, but this is still very well done, especially for a student project.

We did see a submersible drone built using parts from a flying drone. Cool, but not quite the same.

Forget Propellers, Embrace Tentacle-based Locomotion

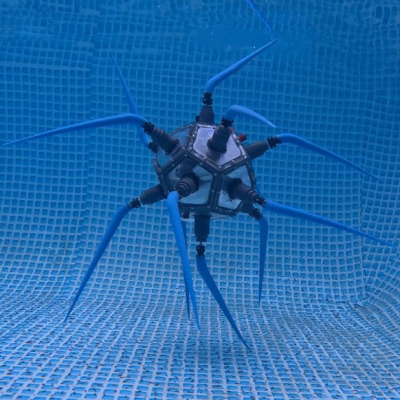

Underwater robots face many challenges, not least of which is how to move around. ZodiAq is a prototype underwater soft robot (link is to research paper) that takes an unusual approach to this problem: multiple flexible appendages. The result is a pretty unconventional-looking device that can not only get around effectively, but can do so without disturbing marine life.

ZodiAq sports a soft flexible appendage from each of its twelve faces, but they aren’t articulated like you might think. Despite this, the device can crawl and swim.

Each soft appendage is connected to a motor, which rotates the attached appendage. This low-frequency but high-torque rotation, combined with the fact that each appendage has a 45° bend to it, has each acting as a rotor. Rotation of the appendages acts on the surrounding fluid, generating thrust. When used together in the right way, these appendages allow the unit to move in a perfectly controllable manner.

This locomotion method is directly inspired by the swimming gait of bacterial flagella, which the paper mentions are regarded as the only example of a biological “wheel”.

How fast can it go? The prototype covers a distance of two body lengths every fifteen seconds. True, it’s no speed demon compared to a propeller, but it doesn’t disturb marine life or environments as it moves around. This method of movement has a lot going for it. It’s adaptable and doesn’t use all twelve appendages at once; so there’s redundancy built in. If some get damaged or go missing, it can still move, just slower.

ZodiAq‘s design strikes us as a very accessible concept, should any aspiring marine robot hackers wish to give it a shot. We’ve seen other highly innovative and beautiful underwater designs as well, like body-length undulating fins and articulated soft arms.

We do notice that since it lacks a “front” — it might be a challenge to decide how to mount something like a camera. If you have any ideas, share them in the comments.

Undersea Cable Repair

The bottom of the sea is a mysterious and inaccessible place, and anything unfortunate enough to slip beneath the waves and into the briny depths might as well be on the Moon. But the bottom of the sea really isn’t all that far away. The average depth of the ocean is only about 3,600 meters, and even at its deepest, the bottom is only about 10 kilometers away, a distance almost anyone could walk in a couple of hours.

Of course, the problem is that the walk would be straight down into one of the most inhospitable environments our planet has to offer. Despite its harshness, that environment is home to hundreds of undersea cables, all of which are subject to wear and tear through accidents and natural causes. Fixing broken undersea cables quickly and efficiently is a highly specialized field, one that takes a lot of interesting engineering and some clever hacks to pull off.

Solving Cold Cases With Hacked Together Gear

People go missing without a trace far more commonly than any of us would like to think about. Of course the authorities will conduct a search, but even assuming they have the equipment and personnel necessary, the odds are often stacked against them. A few weeks go by, then months, and eventually there’s yet another “cold case” on the books and a family is left desperate for closure.

But occasionally a small team or an individual, if determined enough, can solve such a case even when the authorities have failed. Some of these people, such as [Antti Suanto] and his brother, have even managed to close the books on multiple missing person cases. In an incredibly engrossing series of blog posts, [Antti] describes how he hacked together a pair of remotely operated vehicles to help search for and ultimately identify sunken cars.

Continue reading “Solving Cold Cases With Hacked Together Gear”

A Survey Of Long-Term Waterproofing Options

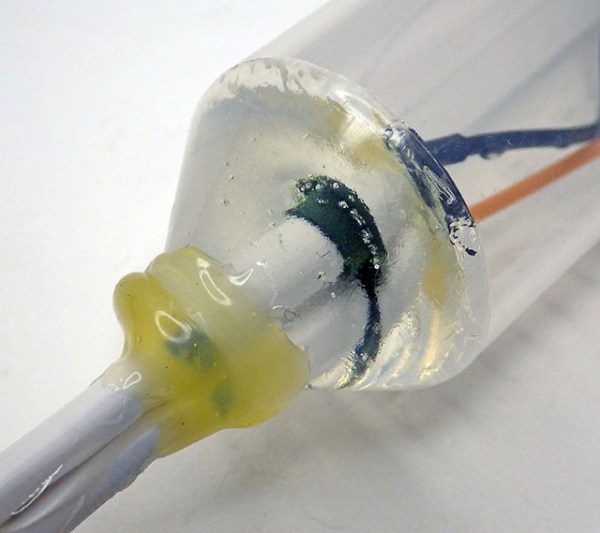

When it comes to placing a project underwater, the easy way out is to just stick it in some sort of waterproof container, cover it with hot glue, and call it a day. But when you need to keep water out for several years, things get significantly harder. Luckily, [Patricia Beddows] and [Edward Mallon] from the Cave Pearl Project have written up their years of experience waterproofing data loggers for long-term deployment, making the process easier for the rest of us.

It starts with the actual board itself. Many SMD boards have at least some flux left over from the assembly process, which the duo notes has a tendency to pull water in under components. So the first step is to clean them thoroughly with an ultrasonic cleaner or toothbrush, though some parts such as RTCs, MEMs, or pressure sensors need to be handled with significant care.

Actual waterproofing starts with a coating like 422-B or nail polish which each have pros and cons. [Patricia] and [Edward] often apply coatings to PCBs even if they plan to otherwise seal it as it offers a final line of defense. The cut edges of PCBs need to be protected so that water can’t seep between layers, though care needs to be made for connectors like SD cards.

Encapsulation with a variety of materials such as hot glue, heat shrink tubing, superglue and baking soda, silicone rubber, liquid epoxy, paste epoxy (like J-B Weld), or even wax are all commented on. The biggest problem is that a material can be waterproof but not water vapor proof. This means that condensation can build up inside a housing. Temperature swings also can play havoc with sealings, causing gaps to appear as it expands or contracts.

Overall, it’s an incredible guide with helpful tips and tricks for anyone logging data underwater for science or even just trying to waterproof their favorite watch.

Continue reading “A Survey Of Long-Term Waterproofing Options”

![[Ben] at workbench with 3D-printed sea scooter](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/sea-scooter-1200.jpg?w=600&h=450)