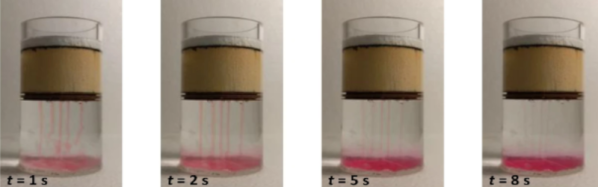

Did you know that water can drip UP instead of down? It’s true! Okay, okay- it’s a bit of an optical illusion, but one that’s mesmerizing no less, and it’s one that is especially awe-inspiring for kids. As [Science Buddies] explains in the video below the break, it’s also achievable for anyone with some basic supplies.

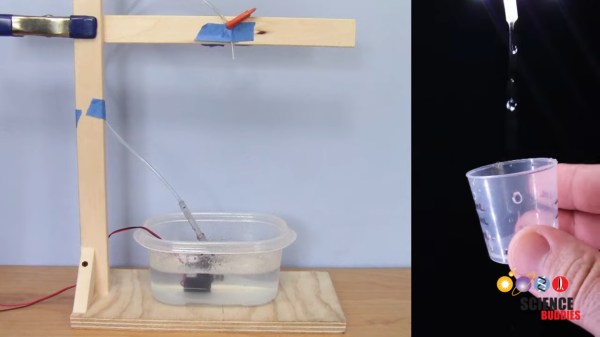

On first glance, the “water dripping upward” illusion looks like it must be extremely complicated with precisely timed drops, and perfectly triggered strobing lights and the like- right? Well, not so much. [Science Buddies] demonstrates a highly simplified experiment using only an aquarium pump, a basic frame, a smart phone with a strobing app, and naturally, water. The experiment is presented in a simple manner that would allow a young person to replicate it without too much adult intervention.

The video goes into such concepts as frequency, duty cycle (pulse width modulation), and other basic engineering principles. The experiment can be completed for just a few dollars for the pump and tubing, and the rest can be improvised. What a great way to get a young one started on their way to engineering!

If you’d like to see a more fleshed out version of a similar machine, check out this gravity defying dripper we featured a few years ago.

Continue reading “Water Drips Up In Kid-Friendly Engineering Experiment”