The ever popular ESP8266 is popping up in more and more projects. There are CNC controllers, blinkey WiFi lighting, and downright bizarre WiFi to Ethernet bridges. [Cicero] has thrown his hat into the ring with one of these Ethernet-enabled ESP8266 builds, and right now everything works, it’s simple to put together, and cheap to build.

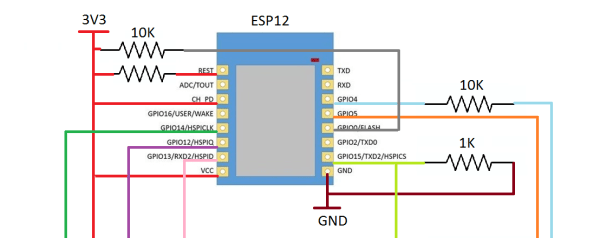

Astute readers will notice we’ve seen something like this before. A few months ago, [cnlohr] discovered the Ethernet controller in the ESP8266. This was, by every account, the hard way of doing things. [cnlohr] was driving the Ethernet directly through the ESP’s I2S bus. [Cicero]’s project does not. It uses the cheap ENC28J60 SPI to Ethernet adapter to put the ESP on a wired network. Is one solution better than the other? That’s arguable. Is one solution much simpler than the other? Yes, [Cicero]’s work allows anyone to add Ethernet to the ESP8266 with a few resistors and a module that costs $3 from the usual online shops.

With the Ethernet stack taken from [Ulrich Radig], the SPI driver from [MetalPhreak], and an ESP8266-based web server from [Sprite_tm], [Cicero] managed to serve up web pages through both the wired and wireless connections.

Although this build is not as technically amazeballs as [cnlohr]’s work with driving Ethernet directly from the ESP, it is very easy to implement, opening up the doors to a few of the more interesting capabilities of a wired ESP. With the Ethernet unlocked, there’s a free WiFi interface to wardrive, snoop around in promiscuous mode, inject packets, bridge a bunch of ESPs in mesh mode to another network, and other network shenanigans. The ENC28J60 modules have probably already found their way into a few parts bins and junk boxes already, making [Cicero]’s work the quick start guide to wired networking on the ESP.

Thanks [PuceBaboon] for sending this one in.

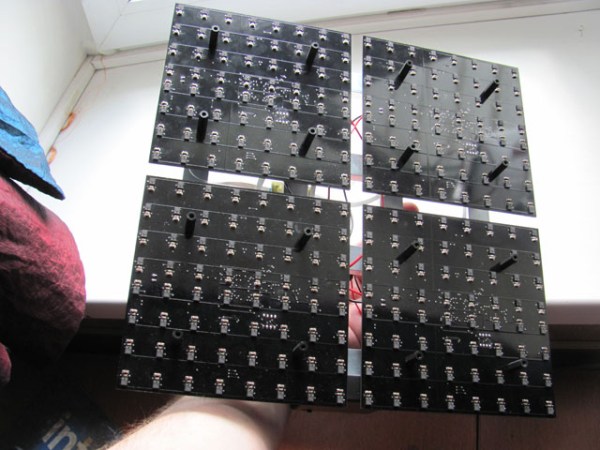

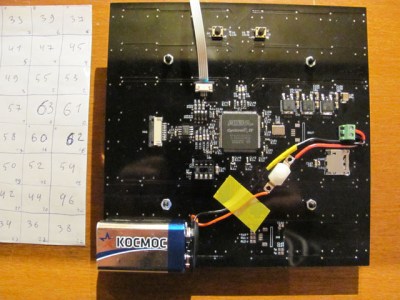

[Artem]’s camera microphone is constructed out of several modules, each of them consisting of an 8×8 array of MEMS microphones, controlled via FPGA. These individual modules can be chained together, and the ‘big build’ is a 32×32 array. After a few problems with manufacturing, the board actually worked. He was recording 64 channels of audio from a single panel. Turning on the FFT visualization and pointing it at a speaker revealed that yes, he had indeed made a sound camera.

[Artem]’s camera microphone is constructed out of several modules, each of them consisting of an 8×8 array of MEMS microphones, controlled via FPGA. These individual modules can be chained together, and the ‘big build’ is a 32×32 array. After a few problems with manufacturing, the board actually worked. He was recording 64 channels of audio from a single panel. Turning on the FFT visualization and pointing it at a speaker revealed that yes, he had indeed made a sound camera.