For decades, astronauts have been forced to endure space-friendly MREs and dehydrated foodstuffs, though we understand both the quality and the options have increased with time. But if we’re serious about long-term space travel, colonizing Mars, or actually having a restaurant at the end of the universe, the ability to bake and cook from raw ingredients will become necessary. This zero-gravity culinary adventure might as well start with a delicious experiment, and what better than chocolate chip cookies for the maiden voyage?

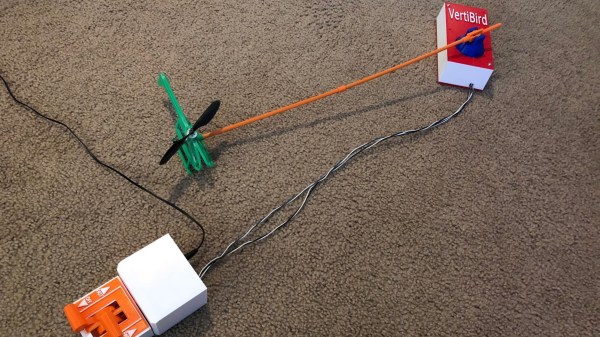

The vessel in question is the Zero-G Oven, built in a collaboration between Zero-G Kitchen and Nanoracks, a Texas-based company that provides commercial access to space. In November 2019, Nanoracks sent the Zero-G oven aloft, where it waited a few weeks for the bake-off to kick off. Five pre-formed cookie dough patties had arrived a few weeks earlier, each one sealed inside its own silicone baking pouch.

The Zero-G Oven is essentially a rack-mounted cylindrical toaster oven. It maxes out at 325 °F (163 °C), which is enough heat for Earth cookies if you can wait fifteen minutes or so. But due to factors we haven’t figured out yet, the ISS cookies took far longer to bake.

Continue reading “First Space Cookies: Cosmic Cooking Is Half-Baked”