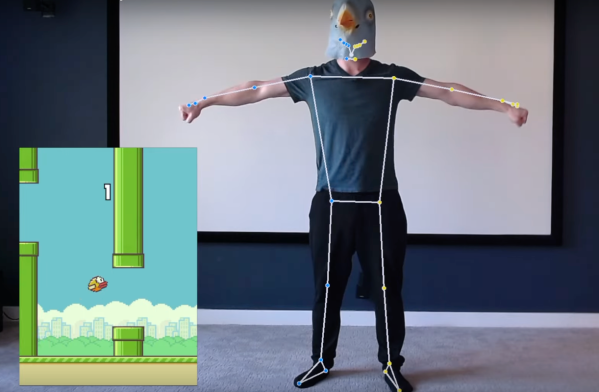

As virtual reality continues to make headway into the modern zeitgeist, it is still lacking in a few key ways. There’s not yet an accepted standard for correlating body motion to movement within a game, with most of the mainstream VR offerings sidestepping this problem by requiring the user to operate some sort of handheld controller to navigate the virtual world. And besides a brief Kinect fad from the 2010s, there hasn’t been too much innovation in this area. But computers have continued to increase in capabilities and algorithms for tracking movement have improved, so [Fletcher Heisler] aka [Everything Is Hacked] leveraged these modern tools into a full-body controller configurable for any video game.

This project builds heavily on a previous project by [Fletcher] which took body position information and turned it into keyboard input, leveraging OpenCV and posture detection software to map keys to specific body positions. It only needed slight modification to work for gaming with regards to the ability to hold down keys or mash buttons, but essentially works by mapping certain keystrokes from the previous project to commands in games. In addition to that step he also added support for multiplayer by splitting the image captured by the camera into two halves so it can keep track of two people simultaneously.