Providing a display for a project in 2020 is something of a done deal. Standard interfaces and off-the-shelf libraries for easily available and cheap modules mean that the hardest choice you’ll have to make about a display will probably relate to its colour. Three decades ago though this was not such a straightforward matter though, and having a display that was in any way complex would in varying proportion take a significant proportion of your processing time , and cost a fortune. [AnubisTTP] has an unusual display from that era, a four-digit LED dot matrix module, and the take of its reverse engineering makes for a fascinating read.

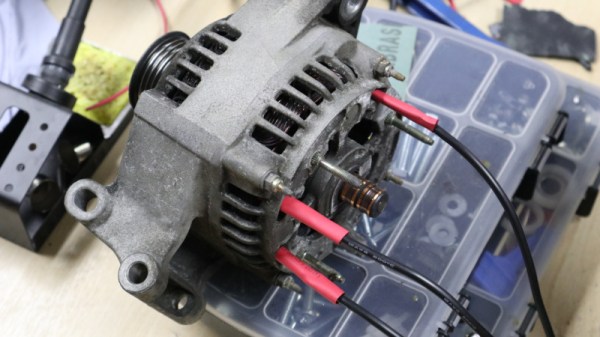

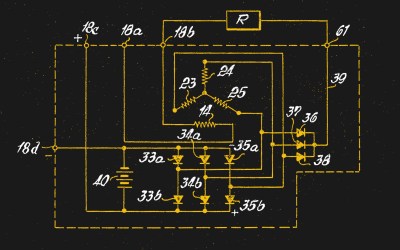

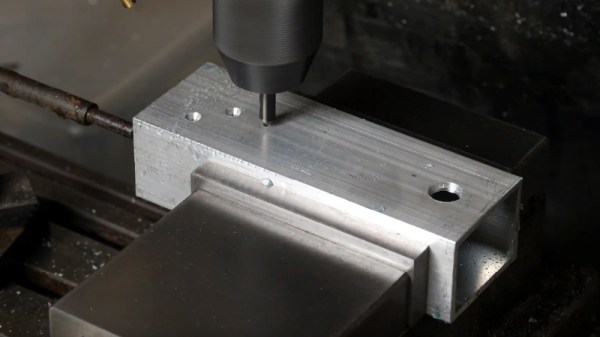

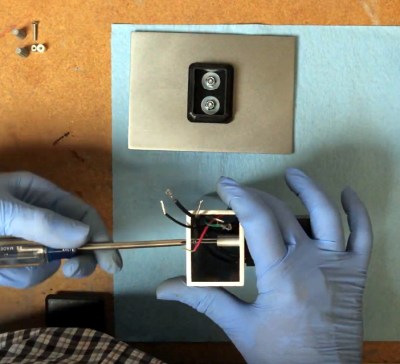

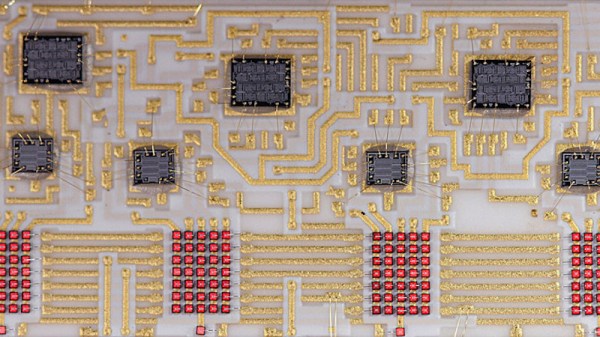

The LITEF 104267 was made in 1986, and is a hybrid circuit in a metal can with four clear windows , one positioned over each LED matrix. Inside are seven un-encapsulated chips alongside the LED matrices on a golf plated hybrid substrate. The chips themselves are not of a particularly high-density process, so some high-resolution photography was able to provide a good guess at their purpose. A set of shift registers drive the columns through buffers, while the rows are brought out to a set of parallel lines. Thus each column can be illuminated sequentially with data presented on the rows. It’s something that would have saved a designer of the day a few extra 74-series chips, though we are guessing at some significant cost.

This display may seem antiquated to us today, but it wasn’t the only option for 1980s designers. There’s one display driver from back then that’s very much still with us today.

This might seem like an odd way to spend $62 million, but for SpaceX, it’s worth it to know that the Crew Dragon Launch Abort System (LES) will work under actual flight conditions. The LES has already been successfully tested once, but that was on the ground and from a standstill. It allowed engineers to see how the system would behave should an abort occur while the rocket was still on the pad,

This might seem like an odd way to spend $62 million, but for SpaceX, it’s worth it to know that the Crew Dragon Launch Abort System (LES) will work under actual flight conditions. The LES has already been successfully tested once, but that was on the ground and from a standstill. It allowed engineers to see how the system would behave should an abort occur while the rocket was still on the pad,