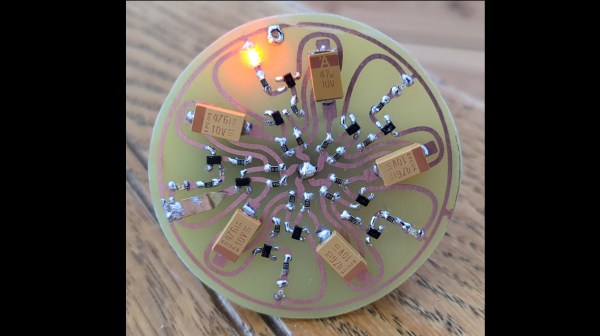

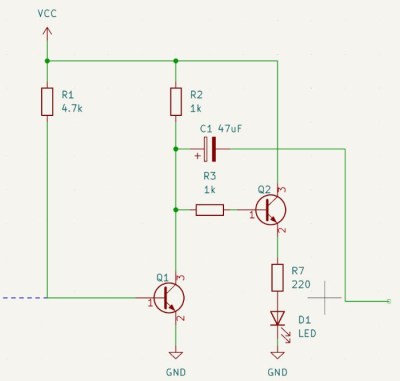

[michimartini] over on Hackaday.io loves playing with multivibrator circuits, and has come across a simple example of a ring oscillator. This is a discrete transistor RC-delay design utilizing five identical stages, each of which has a transistor that deals with charging and discharging the timing capacitor, passing along the inverted signal to its nearest neighbor. The second transistor isn’t strictly needed and is only there to invert the signal in order to drive the LED. When the low pulse passes by the LED lights, without it you’d see all the LEDs lit bar one, which doesn’t look as good.

Essentially this circuit is just the classic astable multivibrator circuit that has been split in half and replicated so that the low pulse propagates through more stages than just the two, but thinking about it as a single stage doesn’t work so well until you draw in a couple of neighbors to help visualize the behavior better.

[michimartini] does lament that the circuit starts up in a chaotic fashion and needs a quick short applying to one transistor element in order to get it to settle into a steady rhythm. Actually, that initial behaviour could be interesting in itself, especially as the timing changes with voltage and temperature.

Anyway, we like the visual effect and the curvy organic traces. It would make a neat pin badge. Since we’re thinking about blinkies, here are couple of somewhat minimalist attempts, the world’s smallest blinky, and an even smaller one. Now, who doesn’t love this stuff?

Continue reading “PentaBlinky – When One LED Is Not Blinky Enough”